Get the 90-day roadmap to a $10k/month newsletter

Creators and founders like you are being told to “build a personal brand” to generate revenue but…

1/ You can be shadowbanned overnight

2/ Only 10% of your followers see your posts

Meanwhile, you can write 1 email that books dozens of sales calls and sells high-ticket ($1,000+ digital products).

After working with 50+ entrepreneurs doing $1M/yr+ with newsletters, we made a 5-day email course on building a profitable newsletter that sells ads, products, and services.

Normally $97, it’s 100% free for 24H.

February 15, 1819, Angostura (modern Ciudad Bolívar, Venezuela)

Nearly one million square miles. Larger than Western Europe. Larger than Alaska and Texas combined. A republic stretching from the Caribbean coast across the towering Andes to the Pacific Ocean, encompassing what would become Venezuela, Colombia, Panama, and Ecuador.

This was what one man proposed to create in February 1819—while the war for independence was still raging, while Spanish forces occupied most of the territory he was claiming, while he controlled little more than some river towns and grasslands in eastern Venezuela.

"A divided America is weak," Simón Bolívar declared to the assembled congress in a makeshift hall in Angostura. [1]

He was a Venezuelan-born aristocrat turned revolutionary general, and he was proposing the immediate creation of Gran Colombia, a unified republic that would become one of the largest nations on earth.

For eleven years, against all logic, it worked. And then it spectacularly didn't.

This is the story of the South American nation you've never heard of—one that was larger than Western Europe, that briefly dominated an entire continent, and that collapsed so completely it's been almost entirely forgotten.

Carta XI División política de Colombia 1824, Agustín Codazzi, Manuel Maria Paz, Felipe Pérez, Public domain

The Spanish Empire's Patchwork

To understand Gran Colombia, you need to understand what Spain had created in South America—and what it left behind when independence came.

The Spanish Empire didn't govern South America as one unit. It was divided into viceroyalties, each reporting directly to Madrid. By the early 1800s, the relevant ones were the Viceroyalty of New Granada (covering modern Colombia, Panama, Venezuela, and Ecuador) and the Viceroyalty of Peru to the south. But even within these administrative units, regions operated with substantial independence from each other.

Venezuela's economy ran on cacao and cattle from its coastal plains and inland llanos (grasslands). New Granada's wealth came from gold mines in its mountainous interior, with Bogotá serving as the administrative capital high in the Andes. Quito (in modern Ecuador) was a remote southern province with its own distinct identity, connected more to Peru than to the Caribbean coast.

These regions didn't naturally belong together. What united them was Spanish rule—and after 1810, a common enemy when they all began revolting against that rule.

But winning independence created a new problem: what came next?

Enter Bolívar

Simón Bolívar was born in 1783 into one of the wealthiest families in Caracas, Venezuela. His parents owned plantations, mines, and enslaved people. Orphaned young, he inherited a fortune and spent his late teens and early twenties in Europe, soaking up Enlightenment philosophy and witnessing Napoleon's coronation.

In 1805, in Rome, the 22-year-old Bolívar supposedly climbed Monte Sacro and made a dramatic vow: he would liberate South America from Spanish rule or die trying. [2] It sounds like legend, but it captures the theatrical, idealistic streak that would define his life.

When independence movements exploded across Spanish America in 1810 (after Napoleon invaded Spain and created a power vacuum), Bolívar threw himself into Venezuela's revolution. He was a mediocre military tactician at first—his early campaigns were disasters. But he learned, and more importantly, he developed a vision that extended beyond just winning battles.

Bolívar believed that the fragmented regions of South America needed to unite or they would be picked off by European powers or collapse into anarchy. He looked at the successful United States and saw the power of union. He looked at the squabbling revolutionary juntas across South America and saw weakness.

Gran Colombia was his answer.

Simón Bolívar. byToro Moreno, Luis. 1922, Legislative Palace, La Paz

1819: Declaring a Country That Doesn't Exist Yet

By 1819, the independence wars were going badly. Spain had sent a massive expeditionary force that reconquered most of Venezuela and New Granada. Bolívar controlled little more than some llanos and river towns in eastern Venezuela.

It was from this position of weakness that he made his boldest move.

In February 1819, at the Congress of Angostura, Bolívar proposed uniting Venezuela and New Granada into a single republic. It would be called Colombia (after Christopher Columbus), though history would later call it Gran Colombia to distinguish it from modern Colombia. The congress agreed—at least on paper. The fact that Spain occupied most of the territory was apparently a minor detail to be sorted out later.

Then Bolívar went out and sorted it out.

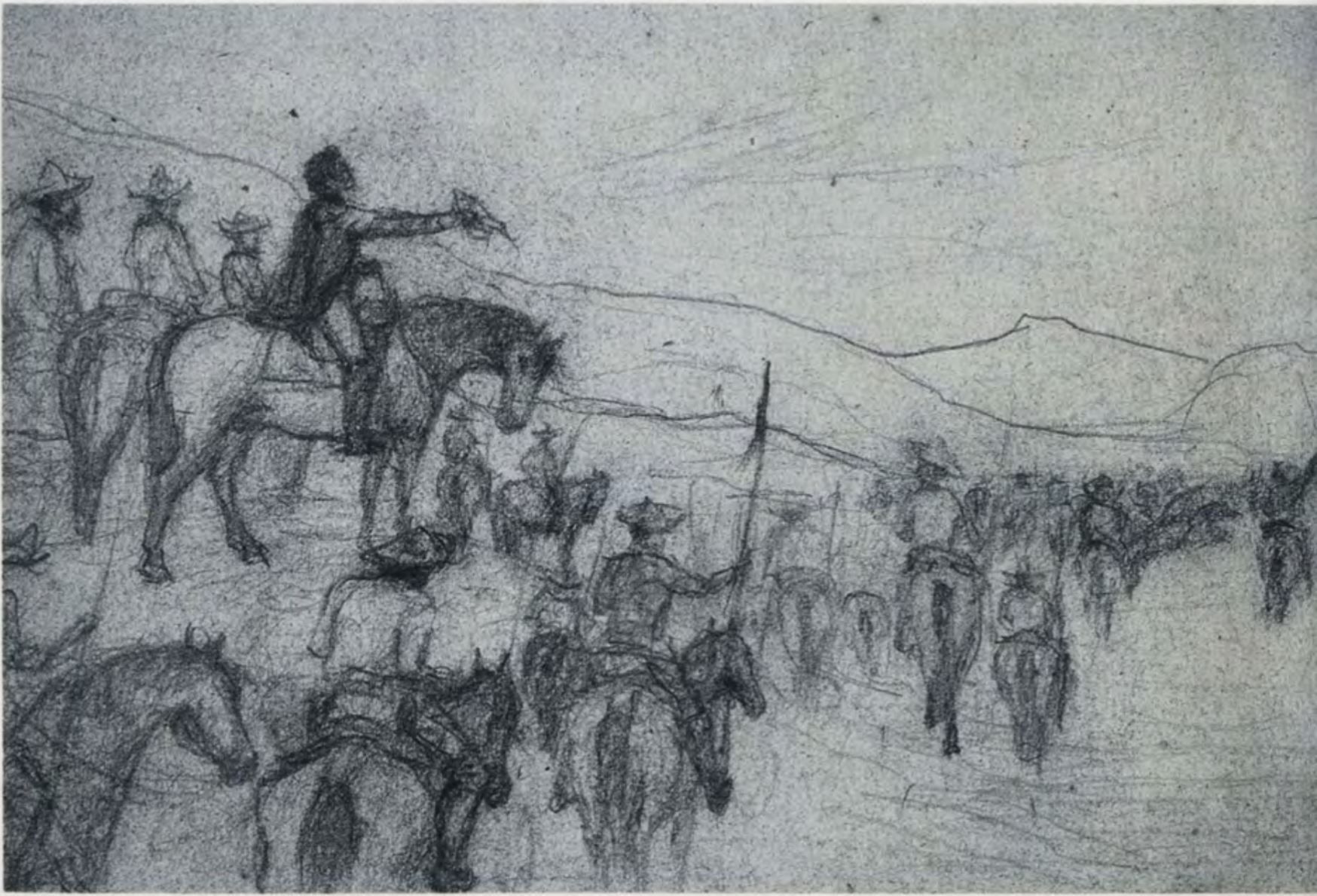

In one of military history's remarkable campaigns, he led his army across the Andes in the rainy season—a route the Spanish considered impassable. His troops, many of them llaneros (plainsmen horsemen from Venezuela's grasslands), suffered terribly in the mountain cold. Hundreds died. But in August 1819, they emerged on the other side and defeated the Spanish at the Battle of Boyacá, liberating Bogotá.

Bolívar and Santander in the battle at Boyaca (1824) by Jose Maria Espinosa

New Granada was suddenly free. Gran Colombia was suddenly real.

In 1821, Bolívar's forces won the decisive Battle of Carabobo, securing Venezuela's independence. In 1822, his lieutenant Antonio José de Sucre defeated the Spanish at Pichincha, adding Ecuador to the union. The Congress of Cúcuta met in 1821 to write a constitution for this new nation, officially establishing Gran Colombia as a centralized republic with Bolívar as president.

On paper, it was magnificent: a nation of roughly two million people stretching from the Caribbean to the Pacific, from the Orinoco river basin across the Andes to the Amazon. A republican government in an age of monarchies. A beacon of Enlightenment ideals.

The problem was, it was almost impossible to govern.

The march of the liberators Bolívar and Santander in the campaign of the Llanos by Jesús María Zamora

The Geography Problem

Picture trying to run a country where traveling between your major cities takes months. Where the capital, Bogotá, sits at 8,600 feet in the Andes, reachable only by mule trails that become impassable in the rainy season. Where news from Caracas (on the Caribbean coast) might take six weeks to reach Quito (in the southern mountains), and another six weeks for a response to return.

There were no roads in any modern sense. No telegraph. Messages moved at the speed of horses and boats. Provincial governors operated with near-total autonomy simply because central government couldn't physically reach them quickly enough to matter.

The Andes weren't just a logistical problem—they were a psychological barrier. People in Caracas had more contact with Caribbean islands than with Bogotá. Quito felt closer to Lima than to Venezuela. These weren't just provinces of one nation—they were separate worlds that happened to share a government.

The Caudillo Problem

Here's where we need to explain a term that defined 19th-century Latin American politics: the caudillo.

A caudillo was a military strongman with a personal army and regional power base. The independence wars had created them by the dozen. These weren't professional soldiers in a national army—they were charismatic leaders who commanded loyalty through personal relationships, military success, and often patronage. Their power came from their followers, not from constitutional authority.

José Antonio Páez was Venezuela's most powerful caudillo. A mixed-race plainsman who'd risen through the ranks, he commanded the fierce llanero cavalry that had been crucial to Bolívar's victories. His power base was the Venezuelan llanos, and his loyalty was to his men first, the nation second.

Francisco de Paula Santander controlled New Granada's central highlands. Unlike Páez, he was an educated lawyer and administrator—but equally powerful in his region.

Juan José Flores dominated Ecuador, a Venezuelan-born general who'd settled in Quito.

These men had won independence. They had armies. They had regional support. And they increasingly had different visions for what Gran Colombia should be.

The Federal vs. Central Debate

The fundamental question was: what kind of nation was Gran Colombia?

Páez and the Venezuelans wanted a federal system—strong regional governments with significant autonomy. This made sense for Venezuela, which had its own economic system (export agriculture) and didn't want to be taxed to pay for Bogotá's bureaucracy or Ecuador's development.

Santander and the Bogotá elite wanted a centralized system with power concentrated in the capital. They believed only a strong national government could hold the republic together and resist both internal chaos and external threats.

Bolívar was torn. His political instincts leaned toward centralization—he believed the young republic needed firm guidance. But he also spent much of the 1820s away from Gran Colombia, campaigning in Peru and Bolivia (which he helped create and which was literally named after him). He was president of Gran Colombia but often an absent one.

Into this power vacuum stepped Santander, serving as vice president and de facto ruler. He and Bolívar had fought together, but their relationship curdled. Santander was methodical, legalistic, committed to constitutional process. Bolívar was charismatic, impulsive, increasingly convinced that constitutional niceties were a luxury Gran Colombia couldn't afford.

By the mid-1820s, they barely spoke to each other.

The Economic Problem

Gran Colombia was broke. The independence wars had devastated the economy. Plantations were destroyed, mines flooded, trade networks broken. The new government inherited massive debts from the war and had almost no way to collect taxes across its vast territory.

Different regions had different economic interests that often conflicted:

Venezuela's export economy wanted free trade and low taxes

New Granada's artisans wanted tariff protection from foreign manufactured goods

Ecuador's textile industry was collapsing under competition from British imports

The whole country needed infrastructure development, but there was no money for it

There was no shared economic vision because there was no shared economy. Venezuela sold its cacao to Europe. New Granada mined gold. Ecuador produced textiles for regional markets. They competed as much as they cooperated.

If this sounds familiar, it should. The European Union faces similar tensions today—wealthy northern states versus struggling southern ones, different economic models forced into one system, regions that benefit unequally from union. Gran Colombia pioneered this dysfunction two centuries earlier, with none of the modern communication or transportation that at least gives the EU a fighting chance.

The Dream Begins to Crack (1826-1828)

By 1826, the fissures were undeniable. Venezuela was in open revolt against Bogotá's authority, with Páez defying the central government. Bolívar rushed back from Peru to try to hold things together.

His solution, increasingly, was authoritarianism. He believed constitutional government wasn't working—that the nation needed a strong hand, perhaps even a monarchy, to survive. This horrified the liberals like Santander who'd fought for a republic.

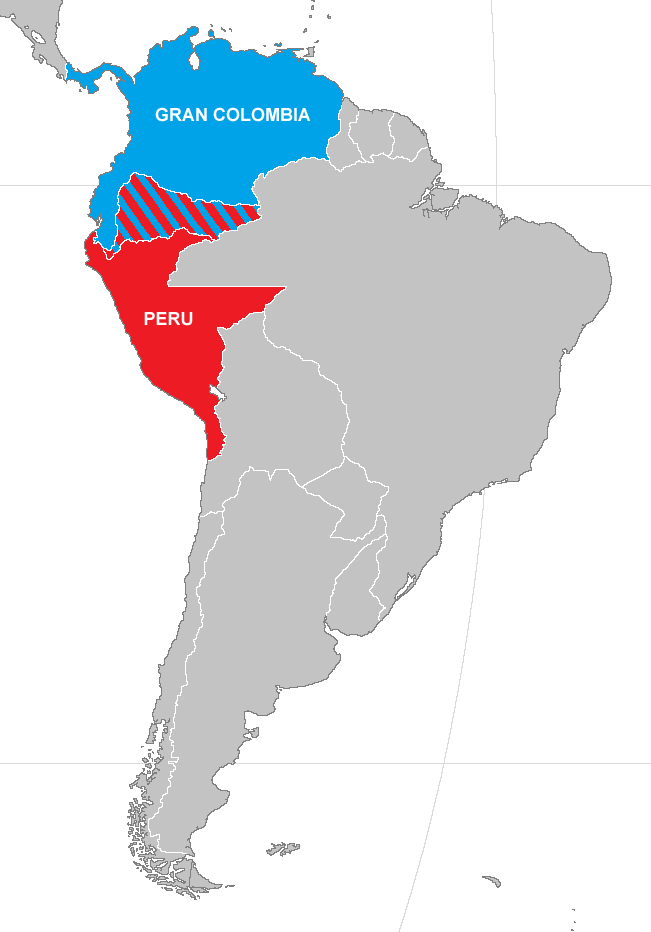

But internal strife wasn't Gran Colombia's only crisis. In 1828, Bolívar declared war on Peru over territorial claims to Jaén and Maynas—regions with contested colonial-era borders. The Gran Colombian-Peruvian War that followed revealed just how overstretched the republic had become. Peru's navy besieged and occupied Guayaquil, one of Gran Colombia's most important ports, in January 1829. Peruvian forces pushed inland, occupying Cuenca. [5]

Map of the disputed territory by Gran Colombia-Peru.

Bolívar's generals, Sucre and Flores, managed to defeat the Peruvian advance at the Battle of Portete de Tarqui in February 1829, but the war dragged on until September. Gran Colombia was now fighting enemies on multiple fronts: Spanish loyalists in some regions, separatist movements in Venezuela, and Peru at its southern border. The strain was crushing.

Meanwhile, domestically, the crisis intensified. In 1828, Bolívar dissolved Congress and assumed dictatorial powers. That September, conspirators—including military officers who'd fought alongside him—tried to assassinate him in Bogotá. He escaped by jumping out a window in his underwear while his mistress, Manuela Sáenz, delayed the assassins. [3] The plot was crushed, but it revealed how many of his former allies now wanted him gone.

Santander, implicated in the conspiracy, was sentenced to death (later commuted to exile). But removing Santander didn't solve the fundamental problem: Gran Colombia was coming apart.

Peru and Gran Colombia map in 1828, Vivaperucarajo

The Collapse (1829-1830)

In November 1829, Venezuela, led by Páez, formally seceded. Ecuador followed in 1830 under Flores. The nation Bolívar had created, that he'd crossed the Andes and fought a continent-wide war to establish, simply dissolved.

Bolívar, now visibly dying from tuberculosis, called a final constitutional convention in January 1830 to try to save what remained. His proposals were ignored. In March, he resigned the presidency with a bitter, prophetic speech. He warned that South America was "ungovernable," that those who served revolution "plowed the sea," and that the continent would descend into chaos under petty tyrants. [4]

He was right. Within years, all three successor states were embroiled in civil wars and dictatorships.

Bolívar planned to exile himself to Europe but was too ill to travel. He made it only to Santa Marta on the Caribbean coast, where he died in December 1830, age 47, essentially penniless.

Gran Colombia officially ceased to exist that same year. It had lasted eleven years.

Why It Failed

The simple answer is geography. You cannot govern a country the size of Western Europe with 1820s technology when mountain ranges separate your major cities.

But the deeper answer is more interesting: Gran Colombia failed because it was never really a nation. It was a wartime alliance that outlived the war.

The regions had united against Spain, but they had no shared identity, no shared economy, no shared political culture. Venezuela's llaneros had nothing in common with Bogotá's lawyers or Quito's highland farmers. The caudillos who'd won independence were warlords, not nation-builders. They'd fought for liberation, not for union.

Bolívar's mistake—perhaps his tragic flaw—was believing that will and idealism could overcome geography, economics, and human nature. That republican government could be imposed from above. That people who'd just fought for freedom would accept centralized authority because it was rational.

They wouldn't. And they didn't.

The Forgotten Nation

Today, Gran Colombia exists primarily in history textbooks and as a fun fact (did you know Colombia and Venezuela used to be one country?). It left almost no institutional legacy. The three successor states—Venezuela, Colombia, and Ecuador—went their separate ways and never looked back.

Bolívar's trajectory—revolutionary hero to dying exile watching his life's work disintegrate—follows a pattern that would repeat across history. Giuseppe Mazzini spent decades fighting for a unified Italian republic, lived to see Italy unite, but under a monarchy he despised, dying marginalized and bitter in 1872. Robespierre tried to save the French Republic through authoritarian control and ended up guillotined, his republic collapsing shortly after. Even entire states follow this arc: the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, once one of Europe's largest powers, dissolved so completely it was literally erased from maps for over a century.

The idealists who try to force unity rarely live to see their visions survive them.

But the questions Gran Colombia raised never went away: Can you build nations from scratch? What holds a country together besides force? When does regional identity trump national identity? How do you govern when your territory exceeds your capacity?

Latin America would spend the next century struggling with these questions through civil wars, caudillo dictatorships, and failed federations. The dream of a united Spanish America that Bolívar died believing in never came close to reality again.

Gran Colombia was an experiment in revolutionary idealism meeting geographic reality. Reality won. The nation dissolved so completely that most people today don't know it ever existed—a country that was too ambitious, too large, and too idealistic to survive the world as it actually was.

Bolívar freed six nations from Spanish rule. He united three of them into Gran Colombia. Both the liberator and his creation died in 1830—the nation dissolving in the same year its founder took his last breath.

FOOTNOTES:

[1] From Bolívar's Angostura Address, February 15, 1819. Full text available at The Liberator: Writings of Simón Bolívar

[2] The Monte Sacro Oath is documented in various biographies, though its exact wording is debated. See: Lynch, John. Simón Bolívar: A Life. Yale University Press, 2006.

[3] The September 25, 1828 assassination attempt is well-documented. Manuela Sáenz's role earned her the title "Liberatrix of the Liberator." See: Murray, Pamela. For Glory and Bolívar: The Remarkable Life of Manuela Sáenz. University of Texas Press, 2008.

[4] Bolívar's final proclamation and his famous "plowed the sea" statement appear in his letters from 1830. See: Bolívar, Simón. Selected Writings of Bolivar, compiled by Vicente Lecuna, edited by Harold A. Bierck Jr. Colonial Press, 1951.

What's Next in Obscurarium?

What bizarre historical phenomenon should we investigate next? Drop us a line at [email protected].