The wooden walls remember everything.

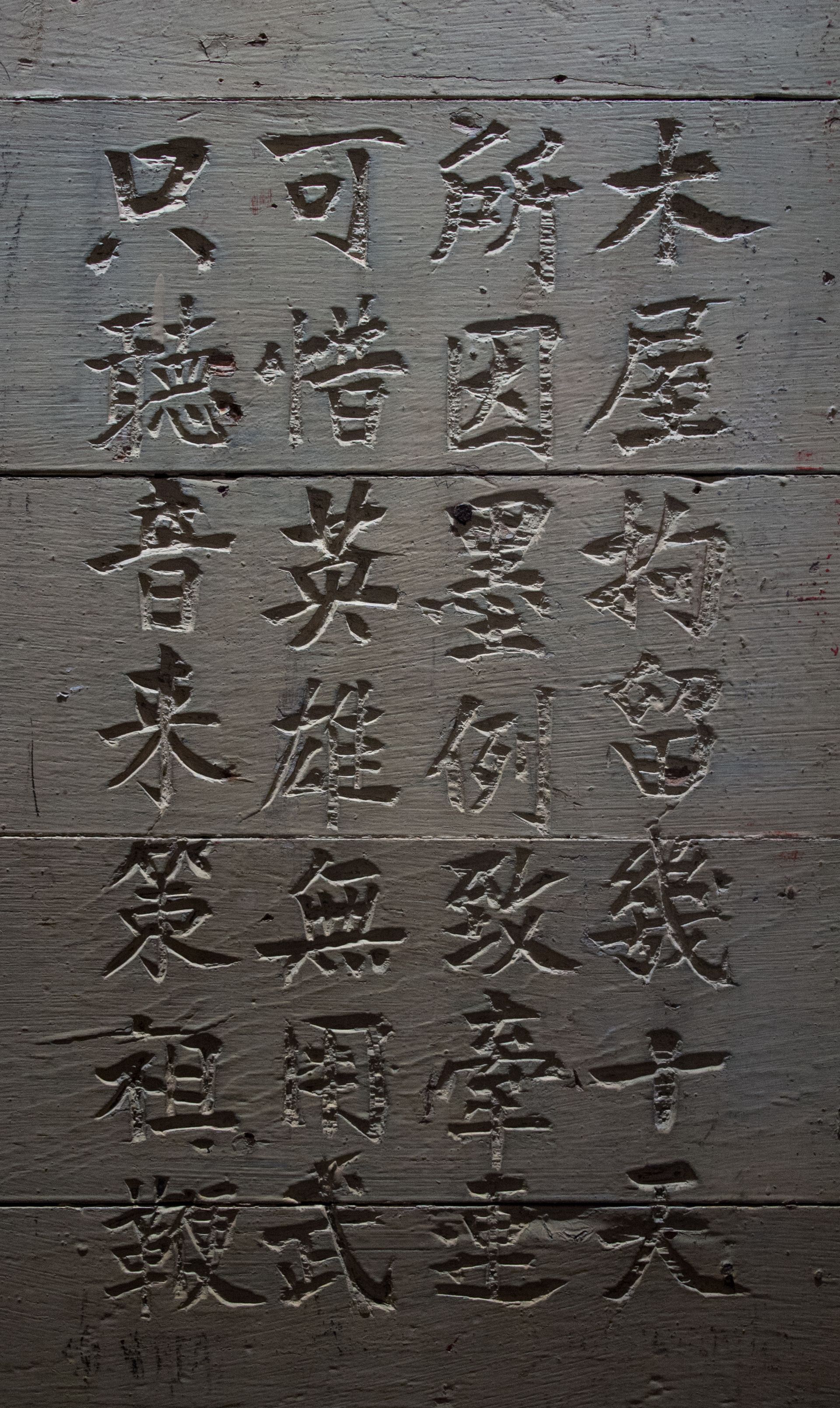

In 1970, a park ranger named Alexander Weiss walked through the abandoned barracks on Angel Island in San Francisco Bay and noticed something strange. Carved into the walls, layer upon layer, were Chinese characters. Poems. Hundreds of them. They'd been there for decades, hidden under paint and plaster, written in classical Chinese verse—four, five, or seven characters per line, following Tang dynasty traditions—by people who had been detained, sometimes for months, sometimes for years, waiting to enter America. 1

One poem reads:

"America has power, but not justice.

In prison, we were victimized as if we were guilty.

Given no opportunity to explain, it was really brutal."

Another:

"I thoroughly hate the barbarians because they do not respect justice."

These weren't criminals. They were immigrants who had committed the crime of being Chinese.

Poetry_on_the_wall_at_the_Angel_Island_Immigration_Station_(2)_(40205)_Rhododendrites, CC BY-SA 4.0 httpscreativecommons.orglicensesby-sa4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Before the Ban: Gold and Railroads

The first Chinese immigrants arrived in the United States around 1815, mostly merchants and sailors.2 Their numbers remained tiny—only 325 by 1848. Then came the California Gold Rush. In 1849, 323 Chinese arrived seeking fortune. By 1850, that number jumped to 450. In 1852 alone, 20,000 came. 3 Between 1849 and 1882, approximately 300,000 Chinese entered the United States.4

They weren't just gold seekers. Chinese laborers built the western portion of the transcontinental railroad, working the most dangerous jobs—blasting tunnels through mountains, hanging from cliffs in wicker baskets to set explosives. They worked California's farms, opened laundries and restaurants, built irrigation systems. They were integral to the infrastructure of the American West.

John_Chinaman_on_the_Railroad,_from_Robert_N._Dennis_collection_of_stereoscopic_views_New York Public Library, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Then the economy collapsed.

The Long Depression hit in 1873, lasting until 1879. Unemployment soared. Wages dropped. White workers, desperate and angry, needed someone to blame. They found their target.

"The Chinese Must Go!"

His name was Denis Kearney, an Irish immigrant who became the most influential voice of anti-Chinese hatred in America. As leader of the Workingmen's Party of California in the late 1870s, Kearney gave inflammatory speeches on empty sandlots in San Francisco, whipping crowds into fury. 5 His slogan became ubiquitous: "The Chinese Must Go!"

Kearney blamed Chinese workers for depressing wages, taking jobs, threatening white masculinity. It didn't matter that Chinese laborers were paid far less than whites and often relegated to work no one else wanted. It didn't matter that they'd helped build the very state Kearney was standing in. The rhetoric was simple and effective: economic anxiety channeled into racial scapegoating.

The violence followed predictably. In 1871, before Kearney's movement even peaked, a mob in Los Angeles killed seventeen Chinese residents in one of the largest mass lynchings in American history. 6 In 1877, anti-Chinese riots swept San Francisco. Politicians heard the rage and translated it into policy.

In 1882, Congress passed the Chinese Exclusion Act—the first federal law in American history to ban an entire ethnic group from entering the country.7 It prohibited Chinese laborers from immigrating for ten years. The Act was renewed in 1892, made permanent in 1902, and wouldn't be repealed for sixty-one years.

What_shall_we_do_with_John_Chinaman_1._Irishman_throwing_a_Chinese_man_over_cliff_towards_China;_2._Southern_plantation_owner_leading_him_to_cotton_fields)_PPOC, Library of Congress, Public Domain, via Wikimedia Commons

The Machinery of Restriction

But the 1882 law wasn't quite the total ban its later reputation suggests. There were exceptions: merchants, students, diplomats, teachers, and travelers could still enter. The original law was titled "An Act to Execute Certain Treaty Stipulations relating to Chinese" and the public called it the "Chinese Restriction Act," not "exclusion."8 In fact, tens of thousands of Chinese continued to enter after 1882 by claiming exempt status, and the average number admitted actually increased in the years following 1882.9

Yet this system of exemptions created its own nightmare. If you wanted to enter as a Chinese person, you had to prove you belonged to one of the special classes. Which meant interrogations. Mountains of paperwork. Witnesses who could vouch for you. And if anything—anything—in your story seemed wrong, you were deported.

Angel Island opened in 1910 in San Francisco Bay to process this bureaucratic machinery. Between 1910 and 1940, approximately 56,113 Chinese immigrants and returning residents passed through the station, with upwards of 30% rejected.10 That means roughly 39,000 people made it through over thirty years—an average of about 1,300 per year, a trickle compared to the pre-1882 flow.

The Interrogation

Imagine you're trying to enter the United States in 1915. You've traveled for weeks across the Pacific. You arrive at Angel Island, perhaps hoping for something like the experience you've heard about at Ellis Island on the East Coast.

Ellis Island, despite its reputation, wasn't perfect—about 20% of arrivals were temporarily detained for health or legal reasons, and some immigrants called it "the Island of Tears." 11But most European immigrants were processed in a matter of hours—90% passed through without problems, with only about 2% ultimately rejected. 12

Angel Island was different. You're taken to a detention barracks surrounded by barbed wire. You'll wait here for weeks. Maybe months. The record was 756 days—over two years. 13

Eventually, you're called for your interrogation. An immigration inspector sits across from you with a stack of papers. He asks: How many steps are there from your house to the village well? What direction does your front door face? How many windows in your neighbor's house? What did you eat at the New Year's festival three years ago? Who sat where at the table?

These aren't casual questions. Inspectors have already interrogated the people who claimed to know you—your alleged relatives, your village witnesses. If your answer differs by even a small detail, you fail. You've spent weeks memorizing coaching books with hundreds of facts about a family and a village, trying to match stories with people you may have never met.

One wrong answer—one misremembered window—and you're sent back across the ocean.

The rejection rate at Angel Island hovered around 10-30%, compared to Ellis Island's 2%. The average detention time was 2-3 weeks, but many stayed far longer.14 While European immigrants were largely welcomed, Chinese immigrants were treated as suspects in a crime they hadn't committed.

So they carved poems into the walls of their prison.

"Leaving behind my writing brush and removing my sword, I came to America.

Who was to know two streams of tears would flow upon arriving here?"

4096px-Angel_Island_Immigration_Station_women's_quarters_(40223)_Rhododendrites, CC BY-SA 4.0 httpscreativecommons.orglicensesby-sa4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Paper Sons and Burned Records

The system should have been airtight. Then, in 1906, an earthquake struck San Francisco. The city burned for three days. Among the ashes: birth records. Immigration records. Proof of citizenship.

Chinese Americans realized they had an opportunity. If the records were gone, who could prove they weren't citizens? Who could prove they didn't have children born in America before the fire?

An underground economy emerged almost immediately. Chinese American men—many of them merchants in the exempt classes who could travel—would go to China and return claiming to have fathered a son, creating an immigration "slot." These slots could be sold. The buyers would become "paper sons," adopting false identities and memorizing coaching books filled with fabricated family histories.

The coaching books were extraordinary documents. Detailed dossiers about villages you'd never seen, families you'd never met. Photographs. Maps. Genealogies spanning generations. You'd memorize hundreds of facts—the layout of your "father's" house, the crops your "family" grew, the neighbors' names, the location of the outhouse. Every detail had to match the testimony of the person who sold you the slot. These books were destroyed before landing, thrown overboard so they couldn't be used as evidence against you.

Paper sons lived entire lives under false names. They married, had children, built businesses—all while carrying the secret. Their children grew up not knowing their real surnames. When some paper sons were finally able to confess the truth decades later—after immigration law changed in 1965—families fractured. Imagine learning at sixty that your family name was invented, your genealogy was fiction, your grandfather wasn't actually your grandfather.

But that was the cost of trying to be Chinese in America.

Paperson Certificate of identity issued to Yee Wee Thing certifying that he is the son of a US citizen, issued Nov. 21, 1916, necessary after the Chinese Exclusion Act was passed.

The Violence Behind the Law

The bureaucratic cruelty was built on a foundation of violence that had terrorized Chinese immigrants for decades.

Rock Springs, Wyoming. September 2, 1885. White miners, angry about wage competition, attack Chinese workers. They kill twenty-eight people. Burn seventy-five homes. Hundreds of Chinese miners flee into the desert with nothing. When it's over, investigators interview witnesses. Grand juries are convened. Nobody is ever convicted. 15

Tacoma, Washington. November 3, 1886. A mob forcibly expels the entire Chinese population—about 200 people—from the city. The mayor watches. The police watch. The Chinese are marched to the train station and told never to return.

These weren't isolated incidents. They were part of a pattern that the Chinese Exclusion Act legitimized. If the federal government itself said Chinese people didn't belong in America, local communities felt licensed to act accordingly.

The Supreme Court blessed the system. In Chae Chan Ping v. United States (1889), the Court ruled that barring people based on race was constitutional—a matter of national sovereignty. 16 The case involved a man who'd left the United States legally with a government-issued certificate guaranteeing his return. While he was gone, Congress changed the law. When he came back, he was turned away. The Court said this was fine. Sovereignty trumped promises.

Other Asians, Different Exclusions

The Chinese weren't the only Asian group facing restrictions, but the machinery of their exclusion operated differently for others—at least at first.

Japanese immigration followed a different trajectory. In 1907, the United States and Japan reached a "Gentlemen's Agreement" that restricted Japanese labor immigration but—critically—allowed family members of those already in America to join them. 17 This meant Japanese women could immigrate as "picture brides," matched to men through photographs and married by proxy before traveling. Between 1885 and 1924, approximately 180,000 Japanese immigrants came to the continental United States, with another 200,000 to Hawaii. 18 They faced discrimination, segregated schools for their children, and hostility from white laborers, but they could build families and communities in ways Chinese immigrants could not.

Korean immigration began around 1903, with over 7,000 Koreans arriving in Hawaii by 1905, many fleeing Japanese occupation and poverty. 19They worked sugar plantations and faced similar discrimination to other Asian groups, but their numbers remained relatively small.

Filipinos occupied the strangest legal position of all. After the Philippines became a U.S. territory in 1898, Filipinos weren't technically foreign nationals—they were classified as U.S. "nationals" but not citizens. 20 This loophole meant they couldn't be excluded under the same laws that banned other Asians. In the 1920s, thousands of young Filipino men migrated to the West Coast to work farms and canneries. But this loophole closed in 1934 when the Tydings-McDuffie Act reclassified them as aliens and imposed a quota of fifty immigrants per year. 21Fifty. For an entire nation.

The differences in how these groups were treated reveal something important: American exclusion wasn't just racist, it was strategic. The bureaucratic machinery could be calibrated—more restrictive for Chinese, slightly less for Japanese (at least until 1924), temporarily lenient for Filipinos until their utility ran out. But the underlying assumption never changed: Asians were fundamentally unwelcome.

“A_DISTINCTION_WITHOUT_A_DIFFERENCE”_1882_Thomas Nast, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

The Blueprint Expands

The Chinese Exclusion Act didn't remain an isolated policy. It became a template, its language and logic replicated and expanded over the following decades.

In 1917, Congress passed the Immigration Act creating the "Asiatic Barred Zone"—a geographic region stretching from the Middle East through South and Southeast Asia from which virtually no one could immigrate. 22The language mirrored the Chinese Exclusion Act. The bureaucratic structures were identical. The rhetoric about assimilation, disease, and economic threat was recycled nearly word-for-word.

In 1924, the Immigration Act introduced national origin quotas explicitly designed to favor Northern and Western Europeans while minimizing everyone else. 23It also used the phrase "aliens ineligible for citizenship" to effectively ban all remaining Asian immigration, including Japanese. The Japanese government, which had viewed the Gentlemen's Agreement as a sign of diplomatic respect, was deeply offended. The 1924 Act obliterated any distinction between Japanese and other Asian groups.

This exclusionary blueprint wouldn't just apply to Asians. In the 1920s and 1930s, Mexican immigrants faced mass deportations during the "Mexican Repatriation"—forcibly removing hundreds of thousands of people, including U.S. citizens of Mexican descent. In the 1950s, "Operation Wetback" repeated the pattern. Southern and Eastern Europeans faced severe quota restrictions in 1924 designed to preserve America's "Nordic" character. The machinery built to exclude Chinese immigrants—the interrogations, the documentation traps, the detention facilities, the assumption of fraud—was repurposed for each new target.

The administrative infrastructure created for Chinese exclusion became the skeleton of modern American immigration enforcement.

The Long Wait for Repeal

The Chinese Exclusion Act wasn't repealed until December 17, 1943—sixty-one years after it was passed. And it was repealed only because China was a wartime ally against Japan. It looked problematic to maintain an official policy declaring Chinese people unwelcome while Chinese soldiers were dying fighting America's enemies.

The Magnuson Act of 1943 ended the outright ban, but barely cracked the door open. It established an annual immigration quota of 105 Chinese immigrants per year. 24 One hundred five. After more than six decades of near-total exclusion, America grudgingly allowed 105 Chinese people to enter annually. The Act also finally allowed Chinese immigrants to become naturalized citizens—a right that had been denied since 1882.

The poems on Angel Island's walls were nearly lost. The station closed in 1940. The barracks sat abandoned for three decades, scheduled for demolition. But in 1970, when park ranger Alexander Weiss discovered those carved characters hidden under layers of paint, activists fought to preserve them. Today, Angel Island is a National Historic Landmark. You can visit the barracks and see the poems still carved into the wood.

What They Built

The architects of Chinese exclusion—the politicians who drafted the laws, the inspectors who conducted the interrogations, the judges who blessed the system, the mobs who enforced it with violence, the demagogues like Denis Kearney who made careers from stoking hatred—built something that outlasted them by generations.

They created rooms where people waited for years to be judged worthy. They designed questions meant to trap. They legitimized racial bans and exported the model to exclude Japanese, Koreans, Filipinos, Indians, Arabs, Mexicans, Southern Europeans—eventually anyone deemed unsuitable for America. They carved the exclusion into law, backed it with Supreme Court rulings, and made it seem reasonable, even necessary.

What Came After

The real change didn't come until 1965, when the Immigration and Nationality Act abolished the national origins quota system and removed racial barriers to immigration. 25The Chinese American population, which had been artificially suppressed for over eighty years, exploded. Within ten years, it nearly doubled. 26

Today, there are approximately 5.5 million Chinese Americans. They have the highest educational attainment rates in the country—59.7% hold bachelor's degrees or higher, compared to the national average of 33.7%. 27 They've become doctors, scientists, engineers, entrepreneurs, artists, politicians. They've won Nobel Prizes, built companies, taught in universities, served in Congress. The median household income for Asian Americans is $108,710, significantly higher than the national median. 28

This success didn't happen because of America's immigration system. It happened despite a system that spent eighty-three years trying to keep Chinese people out, that subjected them to humiliating interrogations, that imprisoned them on islands, that forced them to live under false names, that legitimized violence against them, that declared them fundamentally unsuitable for American life.

The question isn't just what those who built the exclusion system believed about Chinese immigrants. The question is what the success of Chinese Americans—achieved against such systematic opposition—reveals about how wrong those architects were. About how much America lost during those eight decades of exclusion. About how many contributions were never made, how many lives were never lived, how many families were never formed because the machinery of exclusion was so efficient.

Angel_Island_immigration_station_memorial_Hispalois, CC BY-SA 4.0 httpscreativecommons.orglicensesby-sa4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

The Walls Still Stand

The poems on Angel Island are still there, carved into wood by people who refused to be erased. They're written in classical Chinese verse, following centuries-old traditions. They're beautiful and furious and heartbroken. 29 They were written by people who believed in America enough to cross an ocean, only to be locked in barracks and told they might not be worthy.

"America has power, but not justice."

The walls remember everything. They remember the 756-day detention, the coaching books thrown overboard, the paper sons living under false names. They remember Rock Springs and Tacoma, Denis Kearney's speeches, the Supreme Court declaring racial exclusion constitutional. They remember sixty-one years of being banned, replaced by a quota of 105 per year.

But the walls also bear witness to something the architects of exclusion never anticipated: that the very qualities they feared in Chinese immigrants—their industriousness, their determination, their resilience, their commitment to family and education—would not only persist through generations of systematic oppression, but would flourish once the barriers finally fell. The success of Chinese Americans didn't prove the exclusionists wrong about Chinese character. It proved them right—and exposed the cruelty and waste of trying to keep such people out.

The poems carved into these walls are testimony from people who believed in America enough to cross an ocean and endure years of detention, only to be interrogated like criminals. They understood what the system tried to deny: that no bureaucracy is sophisticated enough, no ban absolute enough, to extinguish human dignity. The walls are still standing. The poems are still there. And so are the descendants of those who carved them.

What's Next in Obscurarium?

What bizarre historical phenomenon should we investigate next? Drop us a line at [email protected].

FOOTNOTES

1 Him Mark Lai, Genny Lim, and Judy Yung, Island: Poetry and History of Chinese Immigrants on Angel Island, 1910-1940 (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1980). The poems follow classical Chinese poetic forms with structured line lengths.

2 Iris Chang, The Chinese in America: A Narrative History (New York: Viking, 2003), 14-17.

3 Ibid., 27-29.

4 Erika Lee, At America's Gates: Chinese Immigration during the Exclusion Era, 1882-1943 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2003), 23.

5 Alexander Saxton, The Indispensable Enemy: Labor and the Anti-Chinese Movement in California (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1971), 113-137.

6 "The Chinese Massacre of 1871," Los Angeles Almanac, accessed November 2025.

7 Chinese Exclusion Act, ch. 126, 22 Stat. 58 (1882).

8 Beth Lew-Williams, "Why Chinese Exclusion Matters (and Why It Doesn't)," OAH Magazine of History, noting that contemporary sources called it the "Chinese Restriction Act."

9 Ibid., noting that tens of thousands continued to enter and average admissions increased post-1882.

10 Lee, At America's Gates, 82-83, 192-194 (Angel Island statistics).

11 "Immigration and Deportation at Ellis Island," PBS American Experience, noting 20% temporarily detained.

12 "At Peak, Most Immigrants Arriving at Ellis Island Were Processed in a Few Hours," History.com, January 31, 2025.

13 Lee, At America's Gates, 82-83 (record detention of 756 days).

14 Ibid., 192-194 (rejection and detention rates).

15 "Rock Springs Massacre," Wyoming State Historical Society, accessed November 2025.

16 Chae Chan Ping v. United States, 130 U.S. 581 (1889).

17 The Gentlemen's Agreement was an informal arrangement negotiated in 1907-1908 between the U.S. and Japan.

18 Roger Daniels, Asian America: Chinese and Japanese in the United States since 1850 (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1988), 100-139.

19 Wayne Patterson, The Korean Frontier in America: Immigration to Hawaii, 1896-1910 (Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 1988).

20 After the Treaty of Paris (1898), Filipinos were classified as U.S. nationals but not citizens.

21 Tydings-McDuffie Act, 48 Stat. 456 (1934).

22 Immigration Act of 1917, Pub.L. 64-301, 39 Stat. 874.

23 Immigration Act of 1924 (Johnson-Reed Act), Pub.L. 68-139, 43 Stat. 153.

24 Magnuson Act, ch. 344, 57 Stat. 600 (1943).

25 Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965, Pub.L. 89-236, 79 Stat. 911.

26 U.S. Census Bureau data on Asian American population growth, 1960-1980.

27 U.S. Census Bureau, 2020 Census data on Chinese Americans.

28 U.S. Census Bureau, Educational Attainment in the United States: 2020. and U.S. Census Bureau, Income and Poverty in the United States: 2020.

29 Lai, Lim, and Yung, Island: Poetry and History of Chinese Immigrants on Angel Island.