Illuminating History's Strangest Corners | Issue #18 | January 2026

One Habit You’ll Keep

By this time of the year, most New Year goals are already slipping. That’s why the habits that last are the simple ones.

AG1 Next Gen is a clinically studied daily health drink that supports gut health, helps fill common nutrient gaps, and supports steady energy.

With just one scoop mixed into cold water, AG1 replaces a multivitamin, probiotics, and more, making it one of the easiest upgrades you can make this year.

Start your mornings with AG1 and get 3 FREE AG1 Travel Packs, 3 FREE AGZ Travel Packs, and FREE Vitamin D3+K2 in your Welcome Kit with your first subscription.

There's a 39-foot-long funeral scroll in the Library of Congress that almost nobody can read.

It's painted on homespun hemp cloth in vivid gouache—103 panels depicting the journey of a dead soul through the afterlife. Past nine black spurs guarded by demons. Through the human domain. Eventually to the realm of gods. But the journey doesn't end there. According to Naxi cosmology, your soul becomes a snake and must navigate back through hell to reach paradise.

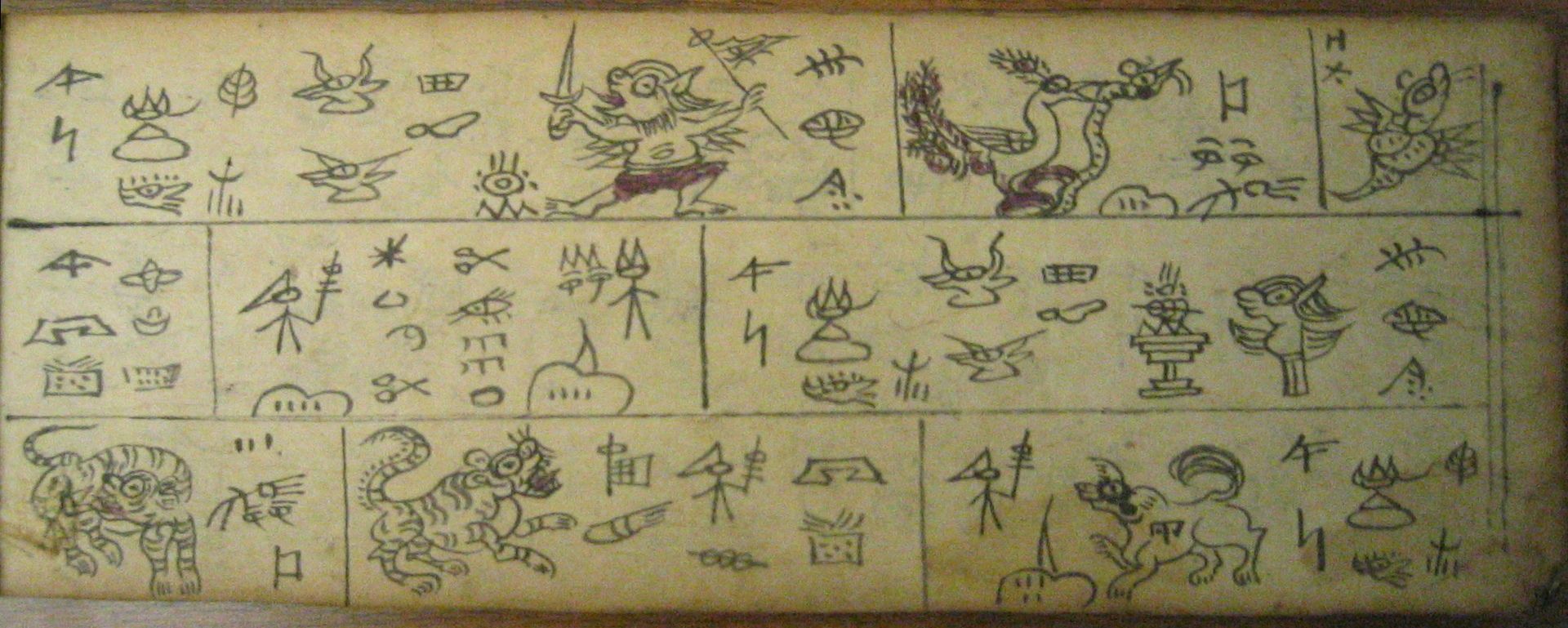

The scroll is written in Dongba script—one of the last pictographic writing systems still clinging to existence. Stick figures with raised arms meaning "pray." Mountains stacked to mean "sacred place." A human lying horizontal with empty eye sockets—no pupils—meaning "dead."

For over a thousand years, only the Dongba priests of China's Naxi people could read these symbols.

Then came the 1960s.

Naxi manuscript

3 Tricks Billionaires Use to Help Protect Wealth Through Shaky Markets

“If I hear bad news about the stock market one more time, I’m gonna be sick.”

We get it. Investors are rattled, costs keep rising, and the world keeps getting weirder.

So, who’s better at handling their money than the uber-rich?

Have 3 long-term investing tips UBS (Swiss bank) shared for shaky times:

Hold extra cash for expenses and buying cheap if markets fall.

Diversify outside stocks (Gold, real estate, etc.).

Hold a slice of wealth in alternatives that tend not to move with equities.

The catch? Most alternatives aren’t open to everyday investors

That’s why Masterworks exists: 70,000+ members invest in shares of something that’s appreciated more overall than the S&P 500 over 30 years without moving in lockstep with it.*

Contemporary and post war art by legends like Banksy, Basquiat, and more.

Sounds crazy, but it’s real. One way to help reclaim control this week:

*Past performance is not indicative of future returns. Investing involves risk. Reg A disclosures: masterworks.com/cd

During China's Cultural Revolution, Red Guards swept through Naxi villages with orders to destroy "feudal superstitions." They found thousands of these manuscripts—delicate books hand-made from tree bark, bound with thread, pages covered in dancing pictographs that recorded a cosmology where humans and nature were siblings, where souls became snakes, where demons guarded the passages between worlds.

The guards could have simply burned them. That would have been ideologically sufficient.

But China was desperately poor, resources were scarce, and pragmatism trumped symbolism. So they reportedly boiled the manuscripts down—thousand religious texts reduced to paste—and used them to plaster the walls of houses.1

The only reason that 39-foot funeral scroll survives? An eccentric Austrian botanist named Joseph Rock had smuggled it out of China decades earlier.

Joseph Francis Charles Rock

THE KEEPER WHO BECAME A THIEF

Joseph Rock was nobody's idea of a typical scholar.

Born in Vienna in 1884, he fled an unhappy childhood and his father's plan to make him a priest, bouncing around Europe before washing up in Hawaii in 1907. He had no university degree. What he had was a gift for languages—he spoke more than half a dozen by the time he reached Honolulu—and an obsessive personality.

He taught himself botany and became Hawaii's first official botanist, producing books that are still considered classics. Then in 1920, the U.S. Department of Agriculture sent him to Southeast Asia to find seeds of the Chaulmoogra tree—a tropical evergreen whose oil was the only treatment for leprosy, a disease that was devastating Hawaii's population2.

Rock's mission succeeded.

But he didn't come home.

In 1922, he arrived in Lijiang, in northwest Yunnan Province where China crashes into Tibet. He'd come for the plants—the region was a biodiversity hotspot with thousands of unknown species.

What he found was the Naxi.

Naxi Stone Village, Rod Waddington, CC BY-SA 2.0

The Naxi weren't some massive ethnic group—maybe 300,000 people clustered in mountain valleys at 8,000 feet elevation. Their location on the ancient Tea Horse Road made them middlemen in one of Asia's most dangerous trading routes, where caravans hauled tea bricks up to Tibet and brought back horses, silver, medicine.

The Naxi had absorbed influences from everyone—Han Chinese, Tibetans, Yi and Bai people—but maintained something entirely their own: Dongba religion and its pictographic script.

Rock became obsessed. He would spend the next 27 years, on and off, living among the Naxi, learning their language, collecting their manuscripts.

Lijiang Yunnan China Naxi people carrying baskets, Photo by CEphoto, Uwe Aranas

A RELIGION WHERE HUMANS AND NATURE ARE SIBLINGS

What made Dongba cosmology fascinating wasn't just the script. It was what the script recorded.

In Naxi creation mythology, Nature and Man aren't master and servant. They're half-brothers, both sons of the creator deity. This siblinghood explains everything: why humans must negotiate with nature rather than dominate it, why mountain gods require offerings (propitiation—gifts to appease potentially dangerous spirits), why the natural world has agency and demands respect.

The Naxi universe is populated by Shv spirits—supernatural beings that are part human, part snake. After death, your soul doesn't ascend to some ethereal paradise. It becomes a snake-spirit and must journey through hell, navigating through nine black spurs guarded by demons, before eventually reaching the realm of gods.

The Dongba priests were the guides for this journey.

When someone died, the family called a Dongba. The priest would arrive with his manuscripts and perform a multi-day ceremony—chanting, dancing, reading from scrolls covered in pictographs. Each funeral was unique, adjusted based on how the person died, their age, their status, the season. The manuscripts provided the framework, but the real knowledge lived in the Dongba's body—decades of apprenticeship, oral traditions, improvisations that made each ceremony a living performance.

440 of the Library of Congress's Naxi manuscripts are funeral rites. Not because funerals were the only ceremony, but because they were the most critical. In Naxi belief, souls go immediately to hell and must be led out. Without proper ceremony, you're trapped there. Forever. As a snake.

THE COLONIAL RESCUE

Rock knew what he was taking.

Between 1922 and 1949, he collected over 8,000 Naxi manuscripts—roughly one-third of all surviving texts. He worked with local Dongba priests to translate them, producing a 1,094-page Naxi dictionary and multiple scholarly works. He sent regular dispatches and photographs to National Geographic, romanticizing the region as a kind of Shangri-La (his writings allegedly inspired James Hilton's Lost Horizon).

But Rock wasn't just documenting. He was extracting. He bought manuscripts from priests. He traded for them. Sometimes he just took them, justifying it as preservation for science.

Naxi Dongba scripture - Yunnan Provincial Museum-DSC02093, Daderot

The Dongba priests were complicit, to a degree. They understood their world was changing. Chinese rule was tightening. Traditional practices faced pressure. Some priests saw Rock as an insurance policy—if the manuscripts left China, they might survive whatever was coming.

They were right. But not in any way they could have imagined.

During World War II, as Japanese forces pushed into China, Rock was in and out of Lijiang, torn between staying for research and fleeing to safety. In 1944, news reached him that a ship carrying decades of his collected manuscripts had sunk. He was devastated. But the Library of Congress had already acquired 1,689 of his manuscripts between 1924 and 1936.

The Roosevelt Connection

The collection grew through another unlikely source: Quentin Roosevelt II, President Theodore Roosevelt's grandson. In 1939, at age 19, Roosevelt traveled to Lijiang on what became a Life magazine-documented adventure.5 His Harvard senior thesis analyzed Naxi manuscripts his father had picked up during a 1927 China trip. Captivated, young Roosevelt collected 1,073 more manuscripts, which he donated to the Library of Congress in 1941. He died seven years later in a plane crash in Hong Kong, aged 29, while working as Director of the China National Aviation Corporation.

By 1949, as Communist forces swept through China, Rock finally left for good. His Naxi assistant—who'd worked with him for years—was labeled an "imperialist dog" and disappeared. Rock settled in Hawaii, continuing his Naxi studies until his death in 1962.

Of the 21,842 Naxi manuscripts that survived into the modern era, Rock personally collected about 7,000 of them—now scattered across American and European institutions. Without his colonial extraction, most would have been destroyed in what came next.

MAO'S CATASTROPHE

Mao Zedong had founded the People's Republic of China in 1949, declaring "Ours will no longer be a nation subject to insult and humiliation. We have stood up."

He was referring to what Chinese nationalists had begun calling the "Century of Humiliation"—a period from 1839 to 1949 when China endured the Opium Wars, colonization by Western powers, the brutal Japanese invasion, and civil war that left millions dead. The term emerged after China's devastating defeat by Japan in 1895 and became central to Mao's founding narrative: the Communist Party had ended China's subjugation.

Mao Zedong sitting, The People's Republic of China Printing Office

By 1958, impatient with the pace of transformation, Mao launched the Great Leap Forward—a wildly ambitious attempt to industrialize China in fifteen years. Tens of millions of peasants were ordered to abandon their fields and build backyard furnaces to produce steel. They melted down farm tools, cooking pots, even train rails.

What came out wasn't usable steel—just brittle, worthless metal riddled with impurities.4

With farmers not farming, grain production collapsed. Between 1959 and 1962, an estimated 15 to 45 million people starved to death—the largest famine in human history. Officials hid the disaster, fabricating reports of record harvests while people ate grass, tree bark, leather. Bodies lay in fields.

The catastrophe humiliated Mao and briefly sidelined him from power.

His response? Double down.

THE ASSAULT ON OLD THINGS

For centuries, China had been a patchwork of religious traditions: Buddhism, Taoism, Confucianism, and countless local folk religions. Tens of thousands of temples dotted the landscape. Monks, nuns, priests, and ritual specialists like the Dongba served as keepers of knowledge, mediators between the human and spirit worlds.

This religious diversity was incompatible with Mao's vision. A socialist state required citizens whose loyalty belonged to the Party alone—not to gods, ancestors, or ancient traditions.

In 1966, Mao launched the Cultural Revolution. Red Guards—mostly teenagers and young adults—swept through China destroying the "Four Olds": old customs, old culture, old habits, old ideas.

In Tibet, they destroyed over 6,000 monasteries—90 percent of all Tibetan Buddhist institutions. Monks and nuns were beaten, killed, or forced to marry. The population of Buddhist clergy plummeted from 600,000 in 1950 to nearly none by 19793. Sacred texts were burned by the millions.

The Jokhang Temple—Tibet's holiest site—was ransacked. The cemetery of Confucius was desecrated. Churches, mosques, temples: closed, looted, demolished.

And here's what haunts: historical texts didn't just burn. They became useful materials in a desperately poor country. Books became shoe soles. Prayer flags became rags. Manuscripts were pulped for construction paste. Destroying religious texts proved your revolutionary credentials AND solved material shortages. Two birds, one stone.

THE NAXI RECKONING

The Cultural Revolution hit Yunnan in 1966. Dongba priests were publicly humiliated, beaten, forced to destroy their own manuscripts. Some burned their libraries rather than face worse. Others were sent to labor camps.

The transmission chain—master to apprentice, stretching back a thousand years—was severed.

By the late 1970s, when China began opening up, most Dongba were dead. The survivors, now in their seventies and eighties, had no one to teach.

1969 Cultural Revolution Poster

WHEN DOCUMENTATION ISN'T ENOUGH

More than 20,000 Dongba manuscripts survived scattered across the world. In 2003, UNESCO designated them part of its Memory of the World Register, noting: "There are only a few masters left, who can read the scriptures. The Dongba literature, except for that which is already collected and stored, is on the brink of disappearing."

After the Cultural Revolution, China launched preservation efforts. The remaining elderly Dongba were celebrated as living national treasures. Scholars recorded them, documented their knowledge.

It didn't save what mattered most.

Books became shoe soles. Prayer flags became rags. Manuscripts were pulped for construction paste.

Today there are perhaps sixty Dongba priests who can read and write the script. Most are over seventy. Xi Shanghong, now in his nineties, spent years working with Leiden University researchers between 2019-2022, looking at digitized manuscripts and dictating their meaning into recording devices, explaining what ceremony each text is for, what ritual actions accompany these symbols.

Young people are learning Dongba now—but in classrooms, from textbooks, at government cultural centers. They can recognize characters. They can copy texts.

But performing a traditional funeral ceremony from memory, with all the improvisations a master would have known instinctively? That knowledge is gone.

The manuscripts are sheet music. The Dongba were the performers. When you lose the living tradition, you lose what notation can never capture.

In Lijiang—now a UNESCO World Heritage Site and major tourist destination—Dongba characters are everywhere. Coffee shops. Souvenir t-shirts. Tour buses. They've become decoration, ethnic branding for tourists to photograph.

The symbols are visible to everyone and readable by almost no one.

Dongba script sample, BrokenSphere, CC BY-SA 3.0

THE PATTERN HASN'T ENDED

Right now, China is detaining over one million Uyghurs and other Turkic Muslims in what it calls "reeducation camps"—the largest mass internment of an ethnic-religious minority group since World War II.

Uyghurs are barred from freely practicing their religion, speaking their language, and expressing fundamental elements of their identity. In 2024, a 26-year-old Uyghur songwriter was sentenced to three years in prison for "promoting extremism"—charges stemming from his artistic work in the Uyghur language and owning books central to his community's cultural history.

In Tibet, increased surveillance, forced separation of children, and political "re-education" continue.

The difference? The Cultural Revolution was chaotic, destructive, driven by revolutionary fervor. Today's campaigns are systematic, bureaucratic, high-tech. Sophisticated surveillance technology monitors people throughout the country to spot any perceived infractions, such as connections with people outside of China or expressions of faith.

The Dongba story isn't just history. It's a pattern that continues.

First, you sever transmission—arrest the teachers, close the schools, separate families, ban the practice. Then you wait. A generation later, what remains is performative, emptied of meaning, safe for museum displays and tourist brochures.

Cultural death doesn't require burning every book. It just requires making sure no one remembers how to read them the way they were meant to be read.

THE COLONIAL PARADOX

Joseph Rock was a colonizer. He extracted cultural artifacts from a community that wasn't his, often without meaningful consent, sometimes through economic coercion. He romanticized the Naxi for Western audiences, turning their religion into exotic spectacle for National Geographic readers.

And he saved half the surviving manuscripts.

Without Rock's colonial extraction, most Dongba texts would exist only as construction paste in houses that probably don't even stand anymore. The priests who sold or gave him manuscripts couldn't have known what was coming—the scale of destruction, the systematic erasure. But they made a devil's bargain that, accidentally, preserved their tradition.

This is the paradox of cultural preservation in the 20th century: sometimes the imperialist is also the archivist. Sometimes extraction is also rescue. Sometimes the only way knowledge survives is by leaving home.

The Naxi didn't choose this. Neither did the Tibetans, the Uyghurs, or any of the other minorities whose cultural artifacts now sit in Western museums because staying in China meant destruction.

Within ten to fifteen years, the last traditionally trained Dongba will be gone. What remains will be documentation, not transmission. Scholars studying artifacts, not practitioners wielding tools.

THE LAST READER

The 39-foot funeral scroll sits in the Library of Congress, protected forever.

And there's almost no one left alive who knows what it says.

Sources:

What's Next in Obscurarium?

What bizarre historical phenomenon should we investigate next? Drop us a line at [email protected].

1 While direct English-language documentation of manuscripts being boiled into paste is difficult to verify, the systematic destruction of religious texts during the Cultural Revolution is extensively documented. Tibetan Buddhist scriptures were used as shoe soles, wrapping paper, and mixed with animal dung; similar treatment of Dongba manuscripts is reported in Chinese sources and oral histories.

2 Chaulmoogra oil was used to treat leprosy, a disease that devastated Hawaii's population in the early 20th century. A young Black chemist named Alice Ball had recently solved the problem of making the oil injectable—a breakthrough story we'll explore in a future issue. Rock's seed collection helped establish chaulmoogra plantations in Hawaii.

3 According to Freedom House and multiple scholarly sources, during the Cultural Revolution, the Chinese Communist Party imprisoned thousands of monks and nuns, destroyed all but 11 of Tibet's 6,200 monasteries, and burned sacred texts. An estimated 600,000 monks and nuns lived in Tibet in 1950; by 1979, most were dead, imprisoned, or had disappeared.

4 The Great Leap Forward (1958-1962) aimed to rapidly industrialize China. Farmers were forced to abandon fields to build backyard furnaces for steel production. The campaign produced mostly worthless metal while grain production collapsed 30 percent. Between 15-45 million people died in the resulting famine—history's largest.

5 Quentin Roosevelt II was Theodore Roosevelt's grandson. After his father picked up some Naxi manuscripts during a 1927 China trip, young Quentin became fascinated. At age 19, he traveled to Lijiang in 1939 and collected 1,073 manuscripts, which he donated to the Library of Congress in 1941. His Harvard senior thesis analyzed these texts. He wrote about his journey in Natural History magazine in April 1940, describing the Naxi as living in "the land of the devil priests." Roosevelt died in 1948 at age 29 when his plane crashed in Hong Kong while he worked as Director of the China National Aviation Corporation.