You've probably adjusted a photo before posting it. Maybe you waited for better lighting, cropped out the mess in the corner, or chose an angle that made you look your best. We all do it. We're not lying exactly—we're just... presenting our best selves.

Now imagine that same impulse, but instead of Instagram likes, the stakes are armies, tax revenue, and political survival. Welcome to the 2,000-year history of how governments count people—and why those numbers have never been quite what they seem.

It's Christmas Day, 1085. William the Conqueror orders a survey of much of England and parts of Wales, demanding to know exactly who owns what in his freshly conquered kingdom.

The result, completed in August 1086, would earn a nickname 50-70 years later that perfectly captured its authority: the Domesday Book.

The medieval pun was deliberate. Just as God's judgment on Doomsday cannot be appealed, neither could this book's pronouncements. Property dispute? Check the book. It says you lose? You lose. End of discussion. As England's treasurer explained in 1179, the book's word "cannot be denied or set aside without penalty."

Think of it as your credit score set permanently in stone—except it also determined who owned your house.

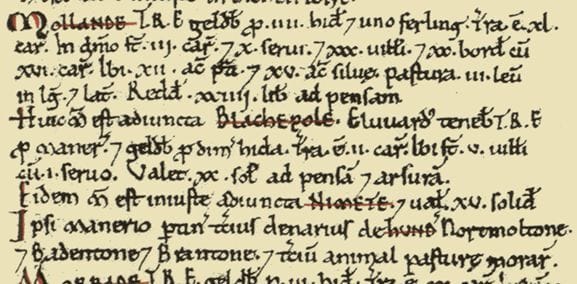

Excerpt of Exeter Domesday Book, 1086

The book catalogued 13,418 settlements, recording who held each piece of land, how many ploughs it had, how many slaves, even how many fish ponds. The survey was ordered to record who held the land and how it was used, and also includes information on how this had changed since the Norman Conquest in 1066.

But here's the thing: William wasn't doing this out of intellectual curiosity.

Needing to raise taxes to pay for his army, the survey was used to assess the wealth and assets of his subjects throughout the land. The Domesday Book wasn't a census—it was a weapon. With it, William could calculate precisely how much tax each region owed, settle disputes over who legally owned contested estates, and—perhaps most importantly—identify exactly which lords could be squeezed for money or threatened with confiscation.

William The Conqueror’s Dominions in 1086

There are some 30,000 manors recorded in the final document and each one was either subjected to a list of questions from the inspectors in person or a self-assessment in writing was studied. Witnesses were called in public sessions to verify all claims and existing documents were consulted to double and triple-check whether the figures were accurate.

Sounds thorough, right?

Except the inspectors were assisted in all this activity by local sheriffs and juries, who were made up 50-50 of Englishmen and Normans to ensure fairness in the disputed or doubtful claims, of which there were thousands.

The very people whose careers depended on staying in William's good graces were the ones verifying the data.

Think about that for a moment. The checkers were the same people who really didn't want to get caught under-reporting assets.

William's book reveals the fundamental tension at the heart of all official statistics: when the people compiling numbers have a stake in how those numbers look, the numbers become negotiable. And that negotiation has taken two primary forms across history.

INFLATING WHAT YOU HAVE

When Votes Became Inventory: Tammany's Golden Age

Fast forward to 19th-century America, where phantom numbers became an art form—not just in New York, but in cities across the nation.

Political machines dominated many American cities from the mid-19th century until the 1960s. During the 19th and early 20th centuries, powerful networks known as political machines typically controlled local votes through cronyism, bribes, and an ability to get out the vote.

But Tammany Hall in New York City was the most famous and longest-lasting, operating from 1789 until the 1950s.

Ball of the St. Tammany Society, NY, Jan. 10th, 1853

In one New York election in 1844, 55,000 votes were recorded even though there were only 41,000 eligible voters. This wasn't a counting error—it was Tammany Hall perfecting techniques that political machines across America were using.

Tammany Hall was the organization that controlled the Democratic Party and most of the votes in New York City. The machine operated through "ward bosses"—local political organizers who wielded power over specific neighborhoods or districts.

If you lived in Ward 7 and needed a job, or a sidewalk fixed, or help with immigration papers, you went to the Ward 7 boss. He'd help you... but in exchange, you and everyone in your family voted exactly how he told you to.

This wasn't purely exploitation.

Tammany Hall helped immigrants and the poor in tangible ways—providing jobs, housing, food, medical care, and coal money during winter.

This created genuine loyalty and gave the machine enormous persuasive power over how people voted. When the ward boss told you to vote five times, you remembered who got you that job.

By the 1860s, William "Boss" Tweed had risen to lead Tammany Hall, perfecting the art of turning social services into political control.

But how was voter fraud even possible on this scale?

The mechanics were surprisingly simple:

As late as the mid-19th century, seven states employed voice voting, a system in which citizens read their choices out loud. Few people carried personal identification. Political parties produced their own ballots, and states only began to adopt the secret ballot in the 1880s and 1890s.

In layman's terms, voting worked like this:

No driver's license needed—you just walked up and SAID your name

Political parties PRINTED their own ballots (not the government!)

The same political party COUNTED the votes

Election inspectors (poll watchers appointed to oversee voting) could be bribed or arrested if they questioned irregularities

Election fraud was so prevalent then that it spawned its own vocabulary—"floaters" were people who cast ballots for more than one party and "repeaters" were those who voted multiple times.

And fraud wasn't limited to one party or one city. Senator Matthew Quay of Pennsylvania, chairman of the Republican National Committee, was convinced that Democrat Grover Cleveland had won the 1884 election because of Tammany's manipulation of votes. Both parties employed these tactics—political trickery wasn't limited to cities; parties cheated in the suburbs and rural areas too.

The Tammany machine didn't just control elections; they manufactured them.

One Tammany operative boasted about his "voting by barber" scheme: "When you've voted 'em with their whiskers on, you take 'em to a barber and scrape off the chin fringe. Then you vote 'em again with the side lilacs and a mustache. Then to a barber again, off comes the sides and you vote 'em a third time with the mustache. If that ain't enough and the box can stand a few more ballots, clean off the mustache and vote 'em plain face."

One man, five votes. Democracy by facial hair.

The Tweed Ring hired people to vote multiple times and had sheriffs and temporary deputies protect them while doing so. It stuffed ballot boxes with fake votes and bribed or arrested election inspectors who questioned its methods. As Tammany leader William "Boss" Tweed himself said, "The ballots made no result; the counters made the result."

Why go to all this trouble? Because those phantom voters translated directly into power—and power meant controlling government contracts, patronage jobs, and tax revenue. More voters on the rolls meant more political clout, which meant more money flowing into party coffers.

The Soviet Union's Industrial Mirage

The impulse to inflate continues into the 20th century—this time with factories instead of ballot boxes.

In the USSR, economic statistics were routinely inflated to meet production quotas and ideological goals. During 1975–1985, data fiddling became common practice among bureaucracy to report satisfied targets and quotas. Factories reported producing goods that were unusable, unfinished, or never produced at all.

Why? Because failure to meet targets could mean demotion, punishment, or worse.

One infamous example: Factories reported producing tons of nails, but to meet weight quotas, they produced uselessly large nails; when quotas shifted to number of nails, they produced tiny ones.

The result: GDP figures that looked impressive on paper, but an economy that was collapsing in reality. After the fall of the Soviet Union, Western economists concluded that Soviet GDP had been overstated—the exact degree is debated, but the systematic inflation of figures is not.

The mechanism was identical to Tammany's ballot boxes: local officials whose careers depended on good numbers were the ones reporting and verifying those numbers.

The Modern Variation: China's Demographic Puzzle

Which brings us to present day—where the same ancient dynamic plays out with digital spreadsheets instead of parchment scrolls.

China's official population in 2023 stood at about 1.41 billion people. But some demographers, particularly those outside China, suggest the real figure could be tens of millions lower. Demographer Yi Fuxian estimates the official count might be inflated by as much as 120-140 million people—roughly 10% of the stated total.

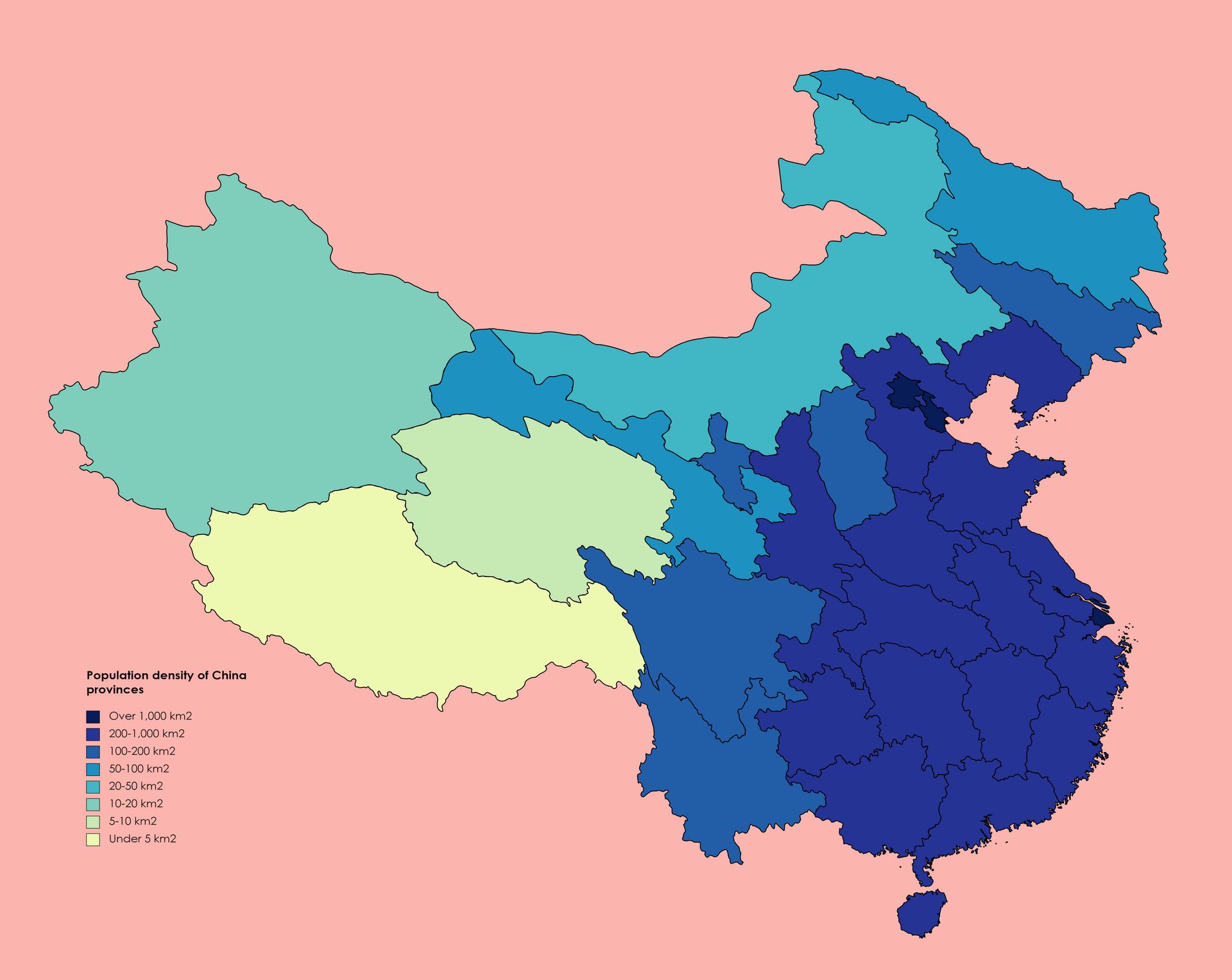

population density of China, Austiger, 2020

How could such a massive discrepancy exist?

China's demographic data flows upward through layers of bureaucracy: household committees report to townships, townships to counties, counties to provinces, and provinces to the National Bureau of Statistics. At each level, officials compile numbers that will partially determine their career prospects and their region's funding.

The system hinges on the hukou—China's household registration system, which is the legal backbone of citizenship. Your hukou determines your access to schooling, healthcare, pensions, and government services. It's like a permanent internal passport that ties you to a specific location and determines what benefits you're entitled to.

And here's where incentives shape reality: local Chinese fiscal systems include central transfers based on population size. More people means larger fiscal transfers for education, pensions, and poverty alleviation funding.

The mechanisms by which "new lives" can materialize on paper include:

Delayed registrations: Not all births are immediately registered through hukou. Some families delay registration to avoid fines (especially during the old one-child policy) or to time eligibility for benefits—housing, schooling, or cash subsidies. When these registrations finally appear—sometimes years later—they can create sudden bumps in reported population.

Cross-agency duplication: Different government agencies (education bureaus, health departments, public security offices) sometimes report population figures independently without fully reconciling duplicates. A child might be counted once by the education system and again by the health system, with no one cross-checking the overlap.

Estimation between census years: Population figures are often estimated rather than measured, relying on local reports rather than verified counts.

Independent verification tells a different story. Nearly all Chinese newborns receive the BCG vaccine, making vaccination distribution a useful proxy for actual births. One analysis using this method estimated that China's reported births may be overstated by about 58 million between 2008 and 2021, with total inflation since the 1980s potentially reaching 178 million people.

The National Bureau of Statistics recognizes local over-reporting and adjusts national figures accordingly, but it lacks direct enforcement power to punish local officials for discrepancies; it mostly does statistical smoothing rather than litigation.

Sound familiar? The inspectors depend on local officials whose careers depend on good numbers. Just like William's sheriffs. Just like Tammany's ward bosses. Just like Soviet factory managers.

HIDING WHAT YOU HAVE

Ancient Rome's Tax Dance

Inflation isn't the only strategy. Sometimes the game is concealment—and Romans mastered this 2,000 years ago.

In ancient Rome, censors conducted comprehensive censuses every four or five years to determine tax obligations. But Rome outsourced tax collection to private contractors called publicani—tax farmers who paid the state upfront, then squeezed provinces to turn a profit.

Historical Map of Ancient Rome of the 1st Century CE.

How it worked in layman's terms:

Imagine your town owes $100,000 in property taxes. A private company pays the government $100,000 upfront, then collects from residents. But they want profit, so they try to collect $150,000. Can't pay? They'll loan you money at 4% per month (48% per year). You're trapped.

The Publicani would lend cash at these exorbitant rates, creating a system where corruption and extortion flourished.

Romans with assets got creative about hiding them. A 1,900-year-old papyrus discovered in the Judean desert tells the story of two men who arranged bogus slave sales to evade taxes. The scheme: create fake paperwork showing they'd sold their slaves, while secretly keeping control of them. When officials demanded proof of previous ownership and tax payments, the men forged documents. They got caught.

The punishment for getting caught? Significant fines, temporary or permanent exile, or hard labour in mines or stone quarries — with the latter essentially a death sentence. In the worst case, one could be made an example of and executed in an imaginative way, such as being thrown to wild beasts in the amphitheatre.

Tax evasion wasn't just a crime—it was treason against the state itself.

Argentina's Inflation That Officially Didn't Exist

Two thousand years later, the concealment strategy evolved but the principle remained.

From 2007 to 2015, Argentina's government systematically manipulated inflation statistics. In January 2007, Graciela Bevacqua, head of the Consumer Price Index, was fired for what she described as her refusal to falsify data on government orders.

Here's why they did it: Argentina had issued billions in inflation-indexed bonds—debt whose payments automatically increased with inflation. Higher official inflation meant the government owed MORE money to bondholders. Pensions and wage negotiations were also tied to official inflation figures.

So the government simply... changed the numbers.

They reported inflation around 10% annually. Independent economists calculated 20-30%. Online price trackers showed Argentina's real inflation was nearly three times the official rate—25% versus the government's claimed 10.6%.

The cost of honesty: If Argentina had reported accurate inflation, it would have owed billions more in bond payments and pensions. By lying, they kept those costs artificially low—essentially robbing bondholders and retirees of their rightful payments while claiming fiscal responsibility.

The fallout: The IMF issued a rare censure in 2013. Independent economists who published alternative estimates were fined and threatened with prosecution. Trust in all official data collapsed. Using adjusted figures, poverty estimates jumped from the official 9.9% to 25.9%—the government had been hiding the suffering of a quarter of its population.

Inflation in Argentina, 1994-2021

Greece's Deficit Disappearing Act

Before the 2008 financial crisis, Greece perfected the art of statistical concealment to gain entry to an exclusive club.

The Maastricht criteria required EU members to maintain a budget deficit below 3% of GDP and public debt below 60% of GDP. Greece wanted in badly—Euro membership meant cheaper borrowing and economic prestige.

So they lied. Repeatedly.

Eurostat (the EU's statistics office) noted that Greek budget deficit and debt had been misreported on no less than 11 occasions since 2000. Greece used complex financial instruments, including cross-currency swaps arranged with Goldman Sachs, to hide debt that European accounting rules didn't require them to report.

In October 2009, a newly elected Greek government dropped the bomb: the country's budget deficit was actually around 12.5% of GDP—more than four times the maximum allowed. The previous government had reported it at just 3.7%.

Greece had been allowed to join the Eurozone in 2001 despite having a budget deficit well over 3% and debt exceeding 100% of GDP. It had simply misrepresented its finances, and European institutions either didn't catch it or looked the other way.

But the false statistics were only part of Greece's problem. The 2008-2009 global financial crisis exposed much deeper vulnerabilities: growing macroeconomic imbalances, large stocks of public and external debt, weak external competitiveness, an unsustainable pension system and weak institutions. From the 1980s onward, explosive expansion of the public sector stifled the private sector, and sixteen years of double-digit fiscal deficits created serious underlying structural economic problems including a bloated public sector.

The revelations about statistical manipulation combined with these pre-existing weaknesses destroyed international confidence. Greece faced a sovereign debt crisis and required EU bailouts totaling hundreds of billions of euros.

The devastating cascade: The country suffered a 26% decline in GDP, unemployment above 25%, and the longest recession of any advanced economy to date. From 2009 to 2015, GDP fell 25% even as Greece increased its discretionary spending surplus by 18%—the austerity cure made the disease worse. Hundreds of thousands of well-educated Greeks fled the country.

Was this fallout solely from fudging numbers? No—but the false statistics prevented early intervention that might have addressed the structural problems before they became catastrophic. By hiding the truth, Greece lost the opportunity for gradual reform and instead faced a brutal, economy-destroying adjustment all at once.

The Eternal Pattern

Whether inflating or hiding, the mechanism is always the same: When numbers determine resources, people make the numbers say what they need them to say.

Medieval England: More land recorded = more tax revenue for the king Ancient Rome: Hide your slaves = lower tax burden Tammany Hall: More votes recorded = more political power Soviet Union: More production reported = career advancement China: More people registered = more central government funding Argentina: Lower inflation reported = lower debt payments Greece: Lower deficit reported = EU membership

Domesday Commissioners at Work 1086 AD. Ernest Prater

The Curated Reality

We started with the metaphor of curating your social media presence—choosing the right filter, the best angle. It seems harmless. You're not lying; you're just showing your best self.

But scale that impulse to nations, and those small adjustments become phantom citizens, ghost voters, hidden slaves, inflated births, concealed debts.

Census taking has never been neutral. It's always been about power—who has it, who wants it, and what they're willing to do to keep it.

Whether you're William the Conqueror tallying manors, a Roman hiding slaves, or a modern state adjusting its numbers, the negotiation is always the same: between what authorities demand to know and what people choose to reveal. Between reported numbers and lived reality. Between official story and hidden truth.

And 940 years after William the Conqueror ordered his great survey, we're still having that same negotiation—still curating our numbers, still presenting our best statistical selves.

The filters have changed. The incentives haven't.

History is often written by victors. But just as often, it is written by accountants—and revised by those who learn how to make the numbers behave.

Further Reading & Sources

Primary Sources:

The Domesday Book Online - Explore the actual 1086 survey

Richard FitzNeal's Dialogus de Scaccario - Origin of the "Doomsday" name explanation

Ancient Rome:

Ancient Roman Tax Fraud Papyrus - The 1,900-year-old case discovered in Judean desert

Roman Publicani and Tax Farming - How Rome's privatized tax system worked

Tammany Hall:

Heritage Foundation: Voter Fraud History - America's political machine era

World History Encyclopedia: Tammany Hall - The rise and methods of Boss Tweed's machine

Modern Examples:

China's Population Debate - Yi Fuxian's demographic analysis

Argentina's INDEC Manipulation - The inflation statistics scandal

Greece's Deficit Crisis - How false statistics contributed to economic collapseWhat's Next in Obscurarium?

What bizarre historical phenomenon should we investigate next? Drop us a line at [email protected].