In the autumn of 1803, twenty-two orphan boys boarded a ship in La Coruña, Spain, bound for the New World. The youngest was three years old. They had been promised adventure, perhaps adoption by wealthy families in the Americas, a chance at a better life than the cold stone walls of the Casa de Expósitos orphanage could offer.

They were not told they would become medical equipment.

Every ten days during the two-month Atlantic crossing, two of the boys would be held down while physicians used a lancet to slice open the pustules on the arms of the previous pair, extracting the precious lymph within, then carving shallow cuts into the next two boys' arms to plant the infection. The boys would develop fevers. Their arms would swell and suppurate. And then, when the pustules were ripe and weeping, the doctors would harvest them again.

The boys were not passengers. They were a living vaccine chain—human links in a biological relay race against time and death itself.

This was the Balmis Expedition, and it may be the most consequential medical mission you've never heard of.

Maria Pita

The Problem: How Do You Keep a Vaccine Alive Across an Ocean?

And how 22 children became human vaccine vessels in history's most ambitious—and ethically troubling—medical mission

By 1803, smallpox had become one of humanity's most reliable killers. In Spain's American colonies, the disease moved through populations like a slow apocalypse, killing up to thirty percent of those it touched. Indigenous populations, with no ancestral immunity, faced even grimmer odds. Entire communities were erased. Children were the most vulnerable—their small bodies offered little resistance to the virus that turned skin into landscapes of pustules, that blinded, that scarred, that killed.

Seven years earlier, an English country doctor named Edward Jenner had made a discovery that would change everything. He noticed that milkmaids who contracted cowpox—a mild disease caught from cattle—never seemed to get smallpox. In 1796, he deliberately infected an eight-year-old boy with cowpox, then later exposed him to smallpox. The boy didn't sicken. Jenner called his technique "vaccination," from vacca, the Latin word for cow.

The vaccine worked. But it came with a cruel limitation.

The cowpox matter—the lymph extracted from pustules—remained viable for only about ten days before it dried out and died. Spain's American colonies lay two months across the Atlantic. No amount of careful preservation could keep the vaccine alive in sealed vials or on threads soaked in lymph, techniques that worked for shorter journeys. The distance was simply too great.

King Charles IV of Spain understood the stakes intimately. Smallpox had killed his daughter. When his physician, Francisco Javier de Balmis, proposed a solution to the vaccine transport problem, the king immediately authorized the expedition and provided royal funding.

Balmis's solution was as ingenious as it was unsettling: if the vaccine couldn't survive the journey, they would create a living bridge. They would carry the vaccine not in vials, but in children.

The Recruitment: Twenty-Two Bodies for Science

The boys came from the Casa de Expósitos, the orphanage in La Coruña. They were expósitos—foundlings, children abandoned at birth, wards of the state and the church. In the rigid social hierarchy of early 19th-century Spain, they occupied the lowest rung. They had no families to object, no voices to protest, no social value beyond what the state assigned them.

The historical record doesn't tell us whether the boys understood what they were volunteering for, or if "volunteering" is even the right word for what happened. We know that Balmis selected boys who had never had cowpox or smallpox—their immunological naivety was essential. We know their ages ranged from three to nine years old. We know their names, or at least some of them: Pascual Aniceto, Martín, Clemente, Fermín, and eighteen others whose names appear in fragmentary records or not at all.

What we don't know is whether they were afraid.

One person accompanied them who had no medical training but whose presence would prove essential: Isabel Zendal Gómez, the rector of the orphanage. Balmis's records barely mention her. She appears in his official reports as merely "the nurse," an afterthought, sometimes not mentioned at all. But Isabel—along with her own son—left Spain with the boys and stayed with them throughout the mission. While Balmis and his team of physicians managed the medical aspects, Isabel managed everything else: the seasickness, the homesickness, the terror of small children far from anything familiar, the fever dreams when the vaccine took hold.

She held them when they cried. She was the only mother most of them had ever known.

The Voyage: Arm to Arm Across the Atlantic

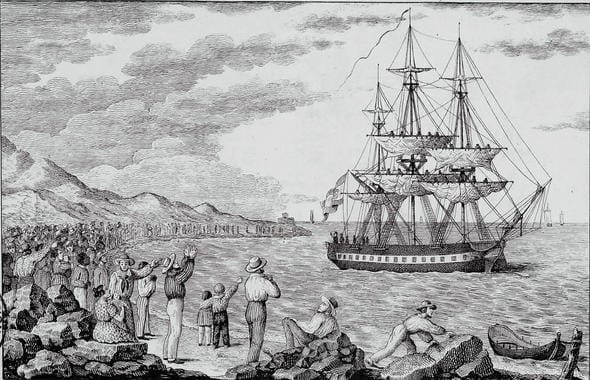

The María Pita sailed from La Coruña on November 30, 1803. In the hold, Balmis had packed medical supplies, lancets, bandages, and detailed instructions from Jenner himself. On deck, the orphan boys began the longest pediatric clinical trial in history.

The method was brutally simple. Two boys would be vaccinated by extracting lymph from the active pustules of the previous pair—usually around day ten, when the vesicles were mature and full of viable vaccine matter. The physicians would make small incisions in the boys' arms and introduce the lymph. Within days, the telltale pustules would appear: raised, fluid-filled bumps at the vaccination site. Fever would follow. The boys would feel ill, their arms swollen and painful.

And then, ten days later, it would be their turn to be harvested.

The chain could not break. If too many boys fell ill at once from other causes, if the spacing was miscalculated, if the pustules were harvested too early or too late, the vaccine would die. The mission would fail. The boys were not just carriers; they were a biological clock, their bodies ticking toward the next link in the chain.

Several boys did fall ill during the voyage—not from the vaccine, but from the ordinary brutalities of early 19th-century sea travel. Dysentery, scurvy, respiratory infections. If one of the boys in the active pair died before his pustules could be harvested, there would be no vaccine to pass to the next link. The margin for error was terrifyingly thin.

The María Pita reached Puerto Rico on March 9, 1804. The vaccine was alive. The boys had succeeded.

But the mission was far from over.

The Expansion: A Human Chain Around the World

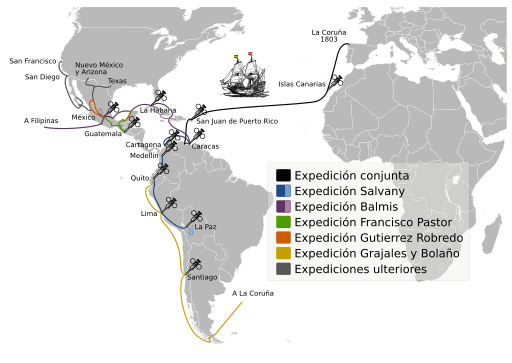

From Puerto Rico, the expedition split into teams, fanning out across the Spanish colonial world like a medical web. Balmis himself headed to Venezuela, then New Granada (modern Colombia), then on to Cuba and Mexico. His subordinate, José Salvany, took another team to South America—Colombia, Ecuador, Peru, and Bolivia. Everywhere they went, they vaccinated thousands.

This was humanitarian work in service of empire. The mission's motives were inseparable from Spain's economic interests: smallpox decimated the labor force that worked colonial mines and plantations. Dead subjects produced no silver, paid no taxes, generated no wealth for the crown. The expedition saved lives, yes—but it saved them to preserve colonial productivity. Spain positioned itself as an enlightened empire deploying modern science for the benefit of its territories, even as those territories remained under Spanish exploitation and control. The vaccine was always free, and Balmis often paid families to vaccinate their children, but the infrastructure of vaccination—the boards, the record-keeping, the administrative oversight—extended imperial reach into the most intimate aspects of colonial life: the bodies of children.

And everywhere the expedition went, they needed more children.

The Spanish orphans could only carry the vaccine so far before they had all been infected and developed immunity. To continue the chain, the expedition needed fresh, unvaccinated bodies. In each colony, local officials rounded up orphans, indigenous children, and the children of enslaved people. These children were vaccinated, their pustules harvested, and the chain continued.

In some places, local elites refused to have their children vaccinated by the same matter that had passed through the bodies of orphans and indigenous children. Class and racial hierarchies shaped even lifesaving medicine. The vaccine was good enough to use, but the children carrying it were not good enough to touch.

Balmis didn't stop at the Americas. In 1805, he sailed from Acapulco to the Philippines, then to Macao and China—the first global vaccination campaign in history. In the Philippines, Filipino children joined the chain. In Macao, Chinese children. The human relay continued.

By the time the expedition concluded in 1806, it had vaccinated an estimated 250,000 to 500,000 people across three continents. It was an unprecedented public health achievement. Edward Jenner, when he learned of the mission's scope, called it "the most noble and extensive expedition in the annals of history."

He never mentioned the children used as vessels. Neither did most historians for the next two hundred years.

The Return Problem: What Happened to the Boys?

This is where the story gets darker, and where the historical record grows frustratingly thin.

Most of the Spanish orphan boys never returned to Spain. Balmis's official reports suggest that some were "adopted" by wealthy families in the colonies—a sanitized way of saying they were given away, their usefulness exhausted. Some may have been placed in local orphanages. Some simply disappear from the record entirely.

We know that Isabel Zendal Gómez and her son stayed in Mexico, where she received a small pension from the Spanish crown in recognition of her service. She died in Puebla around 1810, largely forgotten.

We know that José Salvany, who led the South American branch of the expedition, died of disease in 1810 in Bolivia, worn down by years of travel through some of the world's most challenging terrain.

We know that Balmis himself returned to Spain a hero, received honors from the king, and continued his medical career. He died in 1819.

But the boys—the boys whose bodies made it all possible—vanish from history. We don't know how many survived to adulthood. We don't know if they were told what they had accomplished, if they understood that their scarred arms had helped end one of humanity's greatest plagues. We don't know if they were grateful for their "opportunity" or if they felt used.

We don't know their stories because no one thought their stories worth recording.

The Modern Cold Chain: Technology Without Equity

Today, we no longer need orphan boys to transport vaccines across oceans. We have ultra-cold freezers, phase-change materials, solar-powered refrigeration units, and real-time IoT monitoring systems that track vaccine temperatures from manufacture to injection.[^1] The technical problem that necessitated the human chain in 1803 has been solved with extraordinary sophistication.

And yet: up to 20 percent of vaccination centers and healthcare facilities globally still lack basic refrigeration to store routine vaccines. The World Health Organization estimates that almost half of all vaccines are discarded annually due to cold chain failures—a staggering waste that represents billions of doses and billions of dollars.

We replaced orphan boys with freezers. But the fundamental inequity remains unchanged. Wealthy nations have ultra-cold infrastructure capable of storing the most delicate vaccines at -80°C. Poor nations often lack even basic electricity to power standard refrigerators. The technology exists to solve the cold chain problem completely—we simply haven't chosen to distribute it equitably.

In 1803, the vaccine reached distant colonies on the bodies of expendable children. In 2025, vaccines often fail to reach distant communities because infrastructure investment is deemed too expensive. The barrier is no longer technical. It's political and economic. Some lives, it seems, are still more worth saving than others.

The Legacy: Medical Triumph, Ethical Abyss

The Balmis Expedition succeeded brilliantly at what it set out to do. It delivered a life-saving vaccine across impossible distances using the only technology available at the time. It established vaccination programs throughout the Spanish Empire. It saved countless lives.

It also treated children as medical instruments, as means rather than ends. The boys had no meaningful choice in their participation. They could not consent; they were too young, too powerless, too socially insignificant. They received no lasting benefit—no education, no compensation, no guarantee of care afterward. They were useful until they weren't, and then they were discarded.

This is the paradox at the heart of the Balmis Expedition: it was both humanitarian and exploitative, both progressive and colonial, both lifesaving and deeply unethical by any modern standard.

The expedition anticipated patterns that would repeat throughout medical history.[^2] In the 20th century, orphans and institutionalized children were used to test radiation effects, experimental vaccines, and pharmaceutical drugs—often without genuine consent. The Tuskegee syphilis study left Black men untreated to study disease progression.[^3] The Nuremberg Code, Helsinki Declaration, and modern informed consent laws emerged specifically because of such abuses.[^4]

But in 1803, there was no framework for thinking about medical ethics in these terms. The boys were expendable, and the cause was righteous, and that was enough.

In 1950, the World Health Organization launched its global smallpox eradication campaign, citing the Balmis Expedition as a key historical precedent. The campaign succeeded. In 1980, smallpox became the first human disease ever eradicated—one of humanity's greatest public health achievements.

The orphan boys of the María Pita, whose names we barely remember, whose stories we never recorded, whose arms bore the scars that bridged continents, helped make that possible.

They were children who became medical tools, who were promised adventure and received only utility, who saved hundreds of thousands of lives and were forgotten by history.

This is their story. They deserve for us to remember it—both the triumph and the cost.

The Obscurarium illuminates history's darkest corners. The Balmis Expedition shows us that even our greatest medical achievements can cast long shadows. The question is whether we're willing to look at them.

Footnotes

[^1]: Modern Cold Chain Technologies: Today's vaccine distribution relies on sophisticated infrastructure including ultra-low temperature freezers that maintain -80°C (requiring constant electricity and backup power systems); Phase Change Materials (PCMs) and specialized thermal containers that maintain ultra-cold temperatures without constant power; battery-driven active cooling systems that offer temperature control and are reusable; IoT sensors and wireless connectivity that continuously monitor vaccine temperatures and alert staff to problems in real-time; cloud-based systems providing 24/7 data flow; and portable refrigeration units with battery-powered cooling that can maintain required temperatures for extended periods without electricity. Despite these technological advances, access remains profoundly unequal.

[^2]: Medical Experiments on Vulnerable Populations: The pattern of using institutionalized children and vulnerable populations for medical experiments continued well into the 20th century. At the Fernald School in Massachusetts (1946-1953), boys with intellectual disabilities were fed oatmeal laced with radioactive iron and calcium in a study conducted by MIT and Quaker Oats researchers; the boys were told they were joining a "science club" and their parents' consent forms never mentioned radiation. At Willowbrook State School in New York (1956-1970), children with intellectual disabilities were deliberately infected with hepatitis to study the disease and test vaccines; parents were told participation was required for admission or that their children would receive better care—a form of coercion. Throughout the 1950s-60s, experimental vaccines were routinely tested on institutionalized children in orphanages and reform schools, often without genuine consent. As recently as the 1990s-2000s, at Incarnation Children's Center in New York, HIV-positive children in foster care were enrolled in experimental AIDS drug trials; when foster parents tried to withdraw their children due to severe side effects, some lost custody, and children who refused medication were sometimes given feeding tubes to force compliance.

[^3]: The Tuskegee Syphilis Study: The Tuskegee Study of Untreated Syphilis in the Negro Male (1932-1972) stands as one of the most egregious ethics violations in American medical history. The U.S. Public Health Service recruited 600 Black men in Macon County, Alabama—399 with syphilis and 201 without—and told them they were receiving free healthcare for "bad blood." In reality, researchers never intended to treat them. Even after penicillin became the standard cure for syphilis in 1947, the men were deliberately left untreated so doctors could study the disease's natural progression to death. The men were not told they had syphilis. They were not told treatment existed. They were not given a choice. Many died, went blind, or suffered severe neurological damage. Their wives contracted syphilis. Their children were born with congenital syphilis. The study only ended in 1972 when a whistleblower leaked the story to the press, causing public outrage. In 1997, President Clinton formally apologized on behalf of the nation to the eight surviving participants. The Tuskegee study exemplifies how medical research has exploited vulnerable populations—particularly Black Americans—treating them as subjects rather than patients, as data rather than people.

[^4]: The Nuremberg Code and Declaration of Helsinki: The Nuremberg Code (1947) emerged directly from the Nuremberg Trials, where Nazi doctors were prosecuted for conducting horrific medical experiments on concentration camp prisoners without consent. Prisoners were subjected to freezing experiments, high-altitude experiments, infectious disease experiments, and surgical procedures—all without anesthesia, all without choice. The Nazi physicians defended themselves by arguing there was no international law governing medical experimentation. The judges rejected this defense and established ten principles for ethical human experimentation, the first and most fundamental being: "The voluntary consent of the human subject is absolutely essential." The Declaration of Helsinki (1964) was adopted by the World Medical Association as a more detailed ethical framework building on Nuremberg. It established principles still central to medical ethics today: research must be based on sound science; risks must be justified by potential benefits; independent ethics committees must review research protocols; informed consent is mandatory except in very limited circumstances; vulnerable populations require special protections; and the wellbeing of research subjects must always take precedence over the interests of science and society. The Declaration has been revised multiple times (most recently in 2013) to address new challenges. These frameworks represent medicine's ongoing attempt to reckon with its history of exploitation—to ensure that what happened to the Balmis orphans, the Tuskegee men, and countless other vulnerable subjects never happens again.

What's Next in Obscurarium?

What bizarre historical phenomenon should we investigate next? Drop us a line at [email protected].