Invest in Renewable Energy Projects Across America

Across America, communities are being powered thanks to investors on Climatize who have committed to a brighter future.

Climatize lists vetted renewable energy investment offerings in different states.

As of November 2025, over $13.2 million has been invested across 28 projects on the platform, and over $3.6 million has already been returned to our growing community of thousands of members. Returns aren’t guaranteed, and past performance does not predict future results.

On Climatize, you can explore vetted clean energy offerings, including past projects like solar farms in Tennessee, grid-scale battery storage units in New York, and EV chargers in California. Each offering is reviewed for transparency and provides a clear view of how clean energy takes shape.

Investors can access clean energy projects from $10 through Climatize. Through Climatize, you can see and hear about the end impact of your money in our POWERED by Climatize stories.

Climatize is an SEC-registered & FINRA member funding portal. Crowdfunding carries risk, including loss.

In the grand theater of financial folly, few acts rival the spectacular rise and catastrophic collapse of the Mississippi Bubble. While its British cousin, the South Sea Bubble, tends to dominate English-language histories, this French financial fiasco of the early 18th century arguably proved even more devastating to its host nation.

Let us journey back to a time when paper fortunes multiplied overnight, when a Scottish gambler became the most powerful financier in Europe, and when an entire kingdom nearly drowned in a deluge of worthless banknotes.

The Stage Is Set

The year was 1715, and the Sun King had set. Louis XIV's death left France financially crippled after decades of extravagant spending and costly wars. The national debt stood at a staggering 3 billion livres—a sum so vast that servicing the interest payments alone consumed nearly 80% of the government's annual revenue.1 The new regent, Philippe d'Orléans, was desperate for solutions.

Enter John Law, a Scottish mathematician, gambler, and economic theorist. Having fled England after killing a man in a duel, Law had spent years wandering Europe, studying banking systems and developing his own theories on money and credit.2 His central insight—revolutionary for the time—was that a nation's prosperity depended not on its gold reserves but on its trade, and that paper money could expand an economy beyond the limitations of precious metals. 3

To the desperate regent, Law's ideas offered salvation.

John Law by Alexis Simon Belle

The Mechanism of Madness

Law's grand scheme unfolded in stages, each more audacious than the last:

First came the Banque Générale in 1716, France's first public bank, authorized to issue paper notes backed by gold and silver. These notes proved immensely popular, offering a convenient alternative to lugging around heavy coins. Within a year, the bank was nationalized as the Banque Royale, with its notes guaranteed by the Crown.4

in August 1717, Law acquired and reorganized the Mississippi Company (officially renamed the Compagnie d'Occident), gaining a trade monopoly over the French territory of Louisiana—a vast, resource-rich land that stretched from the Gulf of Mexico to Canada. Law painted Louisiana as an El Dorado, where gold could be scooped from streams and precious gems gathered by the handful.5 Never mind that most of this territory remained unexplored, its alleged riches existing primarily in Law's fertile imagination.

Through a series of mergers and acquisitions, the Mississippi Company soon controlled virtually all French overseas trade, tax collection, and the minting of coins.6 Law had created not just a company but an empire within a state—what modern observers might call a "too-big-to-fail" institution.

A map of Louisiana and of the River Mississippi, 1721 by Senex

The Fever Takes Hold

As shares in the Mississippi Company went on sale, Law orchestrated one of history's first deliberate stock market frenzies. Initial offerings were limited, creating artificial scarcity. Partial payment schemes allowed investors to secure shares with just a fraction of their value upfront. Company agents spread rumors of gold discoveries and unimaginable wealth flowing from Louisiana.

The result was predictable yet unprecedented in scale. Share prices exploded from their initial 500 livres to over 10,000 livres by late 1719. 7 The narrow Rue Quincampoix in Paris, where trading occurred, became a heaving mass of humanity, where fortunes were made in minutes and servants became richer than their masters by the end of a trading day.

"Millionaires were made by the score," wrote one observer, "and men who had been sweeping streets in May were riding in carriages in December." A hunchback famously earned a fortune by renting out his back as a writing desk for frenzied traders. 8A cobbler near the trading street reportedly earned more money renting chairs and refreshments to traders than he had in years of making shoes.

The Inevitable Collapse

The bubble's bursting began, as such things often do, gradually and then suddenly. By early 1720, some prudent early investors began converting their paper wealth to tangible assets—gold, silver, jewels, land. They'd bought shares at 500 livres, watched them soar to 10,000, and were smart enough to realize this couldn't last. Time to cash out.

Law recognized the mortal danger of this flight from paper. His entire system depended on confidence—confidence that paper shares and paper banknotes held real value. If people started demanding gold and silver in exchange for their paper, the system would collapse. There simply wasn't enough precious metal to back all the paper he'd printed.

So Law did what desperate men do: he made things exponentially worse.

July 1720 promissory note. National Numismatic Collection, National Museum of American History.

In a series of decrees that grew progressively more authoritarian, he tried to force people to keep believing in paper:

February 1720: Gold and silver were officially demonetized. Only paper money was legal tender. Imagine the government declaring your gold coins worthless and insisting you could only use paper bills.

March 1720: Individuals were prohibited from possessing more than 500 livres in coin. Own too much metal currency? You were now a criminal.

Wearing diamonds was forbidden. People had been converting paper into portable jewelry to preserve their wealth. Law banned it.

House searches were conducted to confiscate precious metals. Government agents went door-to-door, seizing gold, silver, and gems.

These desperate measures had the opposite of their intended effect. When a government has to force people at gunpoint to use paper money and ban them from owning gold, it doesn't inspire confidence—it screams that the system is failing. Law was trying to stop a leak in a dam by making it illegal to notice the water.

The panic accelerated.

By May 1720, the system was in free fall. When the government announced a planned devaluation of company shares and banknotes by 50%, riots erupted. Law narrowly escaped with his life as his carriage was attacked in the streets of Paris.

By November 1720, Mississippi Company shares had lost 97% of their peak value. The paper currency backed by these shares became worthless, wiping out the savings of millions. Law fled France disguised as a woman, eventually dying in poverty in Venice nine years later. 9

Satiric German medal minted in 1720 that depicts John Law blowing banknotes, an allegory of the financial bubble of the Mississippi Company that burst that year.

The Aftermath

The collapse of Law's System, as it came to be called, left deep scars on the French economy and psyche. Paper money was discredited in France for generations. The national debt, temporarily relieved during the bubble, returned with a vengeance. Some historians trace a direct line from the financial chaos of the Mississippi Bubble to the fiscal crises that ultimately triggered the French Revolution seventy years later.

Yet John Law's fundamental insights about the relationship between money supply and economic activity were not entirely wrong. His sin was one of excess and poor execution rather than completely flawed theory.

The World Before and After Law

To grasp Law's paradoxical legacy, consider what he walked into. In 1715, France's economy ran on metal—gold and silver coins, heavy and scarce. You couldn't expand economic activity without more metal. France was trapped: drowning in debt but unable to "create" money to solve it, because money meant physical gold you didn't have.

Law proposed something radical: paper money, backed by government promise and theoretically convertible to gold, could circulate as real currency. The money supply could grow to match economic activity rather than being strangled by metal scarcity.

It worked brilliantly—until it didn't.

The problem wasn't the concept of paper money or central banking. The problem was that Law, controlling both the bank (printing money) and the Mississippi Company (whose shares everyone wanted), discovered he could print money to inflate his own stock prices. It was a closed loop with no exit. When people tried to convert paper back to gold, he made gold illegal rather than accepting market reality.

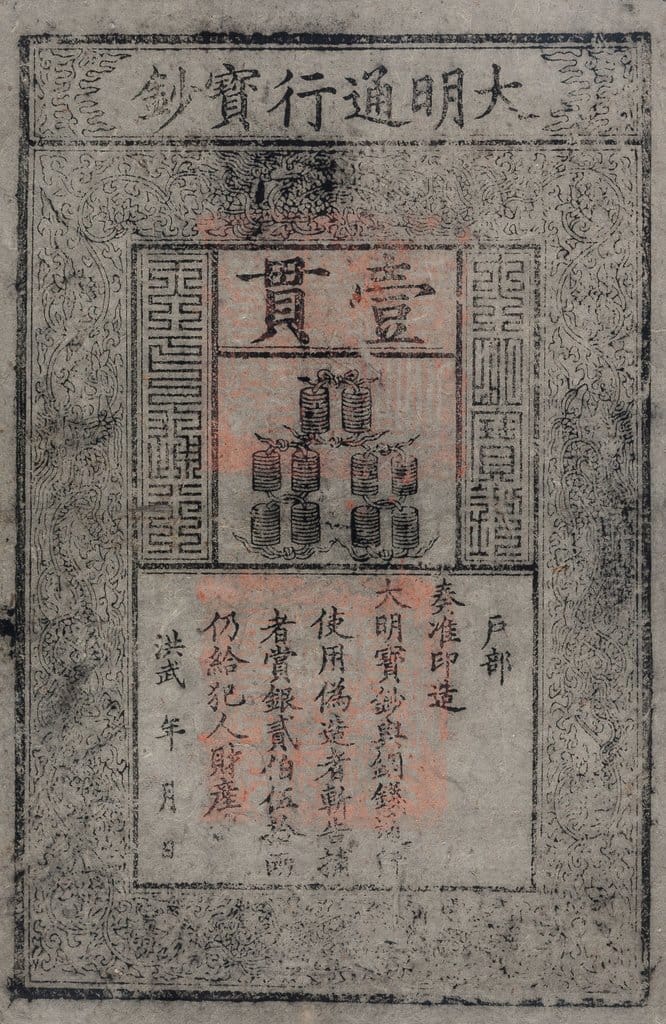

Banknote from The government of the Ming Dynasty, 1368

Law's Shadow Over Modern Finance

The architecture of modern finance—fiat currency, central banks, flexible money supply—incorporates principles Law pioneered and pushed to their logical extremes.

Law didn't invent these concepts. Paper money itself had been used in China centuries earlier, though it had largely disappeared even there by Law's time. In Europe, the Bank of England had existed since 1694. Goldsmith-bankers had been issuing paper receipts that circulated as money since the 1660s. But Law took these scattered innovations and assembled them into an integrated system of unprecedented scale and ambition.

Every major central bank operates on insights Law helped crystallize: that a government institution can manage money supply, expanding it when economies need liquidity, contracting it when inflation threatens. The Banque Royale demonstrated that paper currency backed by government authority, rather than just precious metals, could function as the primary medium of exchange for an entire nation.

Law also pioneered—or at least dramatically scaled—the practice of a central bank purchasing government debt. When his bank bought French government bonds, it created a template that modern central banks still follow, though under very different circumstances and with vastly different safeguards.

When the 2008 financial crisis hit, central banks engaged in "quantitative easing"—creating money to buy government bonds and stabilize markets. The mechanism echoes Law's innovations, even if the intent and oversight differ dramatically.

The critical difference is supposed to be restraint. Modern central banks maintain inflation targets, regulatory oversight, independent mandates. They preserve the appearance—and hopefully the reality—of knowing when to stop.

Law had no such constraints. He printed without limit, manipulated without oversight, and when reality intruded, he tried to ban it by decree. His innovations were sound; his execution was catastrophic. The tragedy of the Mississippi Bubble wasn't that Law's ideas were wrong—it's that they were powerful enough to reshape economies and fragile enough to destroy them when misused.

Echoes Across Time

The Mississippi Bubble stands as a template for financial manias that would follow: the South Sea Bubble (its near-contemporary), the Dutch Tulip mania before it, and countless booms and busts since—from railway stocks to dot-com companies to cryptocurrency surges.

Each time, we convince ourselves that "this time is different," that new technologies or markets have changed the fundamental rules of finance. Each time, we discover anew the truth of Charles Mackay's observation in his chronicle of the Mississippi madness: "Men, it has been well said, think in herds; it will be seen that they go mad in herds, while they only recover their senses slowly, and one by one."10

The Mississippi Bubble reminds us that financial innovation can be both transformative and destructive, that brilliance and folly often reside in the same mind, and that the oldest lesson in finance is also the most frequently forgotten: if something seems too good to be true, it invariably is.

The Bubbler's Kingdom in the Aireal World

What's Next in Obscurarium?

What bizarre historical phenomenon should we investigate next? Drop us a line at [email protected].

1 [1] France's national debt in 1715 stood at approximately 3 billion livres, with interest payments consuming nearly 80% of annual government revenue. Source: Federal Reserve - Crisis Chronicles

2 John Law killed Edward Wilson in a duel over Elizabeth Villiers in Bloomsbury Square, London, 1694. Convicted and sentenced to death, he escaped prison with help from friends. Source: Mississippi History Now

3 Law first proposed his theories in Scotland in 1705 in his work "Money and Trade Considered With a Proposal for Supplying the Nation with Money." Source: Dave Smant's Analysis

4 The Banque Générale was nationalized as the Banque Royale in 1718. Source: Mississippi History Now

5 Promotional materials for the Mississippi Company depicted Louisiana as extraordinarily wealthy, with illustrations showing easy access to gold and gems. Most of the territory remained unexplored.

6 By 1719, Law controlled nearly all French overseas trade, tax collection rights, and coin minting. Source: Mississippi History Now

7 Mississippi Company shares rose from 500 livres in May 1719 to 10,000 livres by December 1719. Source: Federal Reserve - Crisis Chronicles

8 The hunchback story appears in Charles Mackay's "Extraordinary Popular Delusions and the Madness of Crowds" (1841). Modern historians note Mackay's accounts may be embellished but illustrate the frenzy. Source: Wikipedia

9 After fleeing France in December 1720, Law died in poverty in Venice in 1729. Source: Britannica - Mississippi Bubble

10 Mackay, Charles. "Extraordinary Popular Delusions and the Madness of Crowds," (1841). Full text available at Project Gutenberg