Imagine a place where the year is perpetually 1565. Where no cars have ever driven. Where a single man owns the entire island, and you need his permission to live there. Where starlight is a protected resource, and the local lord can be addressed as "Your Seigneur."

Now stop imagining, because this place is real, it's in Europe, and you can visit it tomorrow.

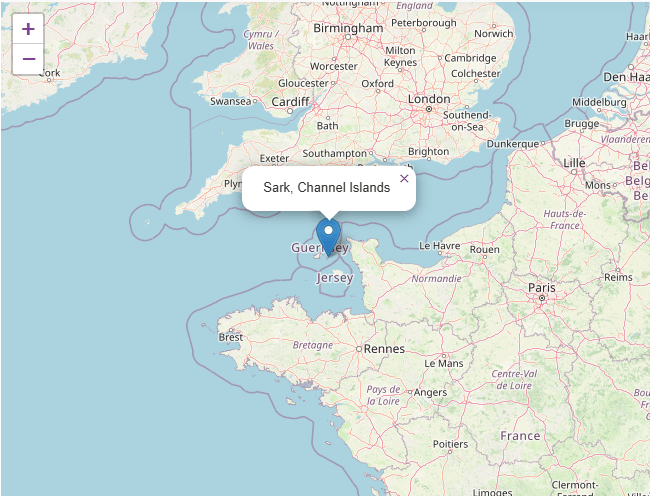

Welcome to Sark, the 2.1-square-mile Channel Island that spent centuries as a time capsule of feudalism—and even after "modernizing" in 2008, remains magnificently, stubbornly anachronistic.

© OpenStreetMap contributors

A Medieval Contract That Never Expired

The story begins in 1565, when Elizabeth I had a problem. French pirates kept using the Channel Islands as a base to raid English ships. The island of Sark sat empty and vulnerable, and the Crown needed someone to colonize it—fast.

Enter Helier de Carteret, a Jersey nobleman who struck one of history's strangest real estate deals. Elizabeth granted him Sark in perpetuity, but with medieval strings attached. He had to bring 40 men to defend it, maintain the island's defenses, and—here's where it gets deliciously archaic—keep "a gun on the island ready to defend it from invasion."

The contract never expired. For 443 years, Sark operated under this feudal charter virtually unchanged. While the rest of Europe guillotined its monarchs, industrialized, and invented democracy, Sark continued as if the French Revolution never happened.

The Rules of an Accidental Time Machine

Until 2008, Sark's government was Chief Pleas—a parliament where 40 hereditary landowners (called "tenants") held automatic seats. These weren't symbolic titles. The Seigneur—Sark's feudal lord—literally owned the island. Want to own property? You needed his permission. Want to divorce? That required the Seigneur's approval too.

The Seigneur collected feudal dues, held unique legal privileges, and was the only person allowed to keep unspayed female dogs and pigeons1. (Yes, really. The pigeon thing was about protecting crops; the dog thing remains mysterious.)

Even today, after democratic reforms, Christopher Beaumont—the 23rd Seigneur who inherited the title from his father in 2016—still holds ceremonial powers that would make any medieval lord envious. He's technically a vassal of the Crown, paying homage to the British monarch while ruling his tiny fiefdom.

Life in the Permanent Past

Here's what makes Sark truly stranger than fiction: the feudal trappings aren't just legal formalities. They shape every aspect of daily life.

No cars. Not "we discourage cars" or "limited cars." Zero. Banned. The island's transportation consists of tractors, horse-drawn carriages, and bicycles. The only motorized vehicles are tractors and an ambulance. Sark does have electricity—it arrived in 1948—but they deliberately chose never to install streetlights. When the sun sets, there's just darkness, stars, and the occasional window glowing from within.

No income, capital gains, inheritance or sales tax. No unemployment benefits. No national health service. Sark operates outside the United Kingdom's tax and welfare systems entirely. It's a self-governing Crown dependency that makes its own rules—funded by property taxes and import duties—and apparently, those rules say "you're on your own."

Population: about 500. Everyone knows everyone. Privacy is a foreign concept. The entire island has one school, one doctor, and one police officer (called a Constable, naturally)2.

The Seigneur still matters. While Beaumont no longer has absolute power, he remains a significant landowner and symbolic figure. The feudal title isn't just a curiosity—it comes with real property and real influence over island affairs.

The 2008 Capitulation (Sort of)

The feudal system finally cracked—not from internal revolution, but from external pressure. The Barclay brothers (owners of The Telegraph newspaper) bought up property on the island and began threatening legal action, invoking European human rights laws against hereditary legislators3. Facing the prospect of expensive court battles, Chief Pleas voluntarily approved reforms in 2008, replacing the feudal system with a fully elected body.

But democracy came with brutal complications. When the Barclay brothers' preferred candidates failed to win seats in the first democratic election, they retaliated4. They shut down their island businesses and fired approximately 140 workers—nearly a third of the island's population. The resulting conflict made headlines as the "Sark Rebellion." The islanders had voted for democracy but discovered that billionaires can punish democratic choices just as effectively as any feudal lord.

Even after reform, Sark residents remain fiercely protective of their anachronistic lifestyle. Cars are still banned. The pace remains medieval. The Seigneur still holds his title5. Democracy didn't so much modernize Sark as get absorbed into its peculiar ecosystem.

What Did the Seigneur Actually Lose in 2008?

The reform stripped away real power from the Seigneur but left the medieval trappings largely intact. Here's what changed—and what didn't:

LOST | KEPT |

|---|---|

Political power: No more veto over island laws, no automatic government role, can't appoint officials anymore | The pigeon monopoly: Still the only person on Sark allowed to keep pigeons. This remains law. |

Control over people's lives: Can't approve or deny divorces, property transfers, or who lives on the island | The title: Still "Seigneur of Sark," still technically a vassal to the British Crown |

The unspayed dog monopoly: Yes, this was repealed. Finally, commoners could keep intact female dogs. | Significant land ownership: No longer owns "the entire island" legally, but still a major landowner with real property rights |

Feudal succession rules: Primogeniture (eldest son inherits everything undivided) was abolished | The mystique: Tourists still visit hoping to glimpse feudal pageantry |

UNCLEAR: Whether feudal dues/property taxes still flow directly to the Seigneur or went to the new democratic government

The takeaway? Democracy ended the Seigneur's ability to actually rule, but couldn't quite kill the feudal aesthetic. Christopher Beaumont is less a medieval lord and more a very fancy landlord with an excellent title.

Getting There (And Surviving There)

Sark isn't hidden or inaccessible—regular ferries run from Guernsey, taking about 50 minutes across the English Channel. Over 50,000 tourists visit annually, stepping off the boat into what feels like a living museum.

But tourism is only part of the economy. The island relies on agriculture too, though in ways that reveal the challenges of maintaining medieval infrastructure in the modern world. Sark has dairy farming—barely. The island needs fresh milk, but operating a profitable dairy on a car-free island of 500 people is nearly impossible. Recently, a Suffolk farming family took over the island's dairy farm, competing in a global search that drew 80 applicants. They lasted a few years before financial losses forced them to quit in 20256.

Most food comes from the mainland. The island produces some of what it needs, but self-sufficiency is a fantasy when you have no cars and limited land. Sark's anachronistic lifestyle depends on regular ferry connections to the modern world.

The Company Sark Keeps

Sark isn't alone in resisting modernity. But compare it to other time-frozen communities, and you realize just how strange its particular anachronism is.

The Amish: Imagine 370,000 people spread across North America who won't own cars, tap into power lines, watch television, use the internet, attend high school, or get divorced. The Old Order Amish live by the Ordnung—an unwritten code governing every detail of daily life. Men wear black broadfall trousers fastened with hooks and eyes (buttons are too fancy). Women can't cut their hair. Couples aren't allowed to kiss, hug, or hold hands before marriage. The catch? They're not rejecting all technology—they're carefully filtering it. Solar panels? Fine. Diesel generators to power washing machines? Sure. But those generators can't connect to the public grid, because dependency on the outside world weakens community bonds. They'll use phones, but keep them in communal "shanties" away from homes. They prosper by selling furniture, produce, and crafts to outsiders while maintaining rigid internal boundaries. It's calculated, theological, and it works.

The Hutterites: Take the Amish communalism and dial it to eleven. Roughly 45,000 Hutterites live on self-sufficient colonies—about fifteen families per colony—where private property barely exists. Most meals are eaten in a communal kitchen. Your modern home? Colony property. Your income? Shared. Religious services happen every evening and twice on Sunday. They practice Gelassenheit—complete self-surrender to the community. Yet they also run mechanized farms with modern equipment and manufacture goods efficiently. They've survived 400 years by making communalism work economically. The Amish filter technology through theology; the Hutterites subordinate individual will to collective survival.

The Sentinelese: Then there's the opposite extreme—50 to 200 people on North Sentinel Island who've had virtually no peaceful contact with the outside world. Stone Age technology. Bows and arrows. No agriculture, just hunting and gathering. The Indian government maintains an exclusion zone, but the Sentinelese enforce it themselves—they kill outsiders who approach. We know almost nothing about them: their language, beliefs, social structure. Unlike Sark, the Amish, or the Hutterites, the Sentinelese haven't chosen anachronism in any conscious sense. They've simply never experienced an alternative, and they violently reject every attempt to offer one.

Sark needs ferries from Guernsey, tourist money, and imported food. Its feudalism isn't theological conviction or Stone Age isolation—it's a real estate contract that aged into quaintness7.

Why It Survives

Here's the strangest part: Sark's feudal quirks aren't a bug—they're the feature. The lack of cars, streetlights, and modern infrastructure makes it one of the world's first designated Dark Sky Islands, where astronomers and stargazers pilgrimage to see the cosmos as medieval peasants did8.

The tiny population and isolated location create a community that, while not exactly egalitarian, has survived in its odd bubble. Tourism sustains the economy, with visitors arriving to experience a place that feels like stepping through a portal.

Sark proves that sometimes the past doesn't die—it just finds a small enough island where the present can't reach it. And as long as people are willing to live by 16th-century rules in exchange for car-free streets and unbroken starlight, the last feudal fiefdom will endure.

The gun Elizabeth I required? Still there, by the way. Just in case those French pirates come back.

Footnotes

This wasn't in the 1565 charter at all—it developed over centuries as one of the Seigneur's traditional feudal privileges. The rule gave the Seigneur exclusive rights to keep female dogs capable of breeding (commoners could only keep males or sterilized females). The modern phrasing "unspayed female dogs" likely only appeared after dog spaying became common in the 1930s—before that, it was probably just "only the Seigneur can keep bitches." Either way, it was a feudal monopoly on dog breeding that persisted absurdly until 2008.↩

Daily life realities: Healthcare means no NHS—the island pays for one doctor. Residents are "strongly encouraged" to get private insurance for hospitalization in Guernsey. Emergencies? You're loaded onto a tractor-drawn ambulance, transported to the harbor, transferred to Guernsey's marine ambulance, and it's 50 minutes by boat to modern medical care. Sark does have high-speed internet though, making remote work viable for those who can afford the lifestyle. ↩

Why the Barclays wanted Sark changed: The twins were extremely reclusive—they bought neighboring Brecqhou to escape public attention entirely. But Sark's feudal laws interfered: they wanted to drive cars on their property (banned), operate helicopters (banned), and divide their estate equally among four children (Sark's primogeniture laws wouldn't allow it). Rather than accept the rules, they decided to change the entire system. ↩

The Sark Rebellion timeline

1993: Barclays buy Brecqhou, build castle

1990s-2000s: Buy up Sark hotels, shops, estates

Mid-2000s: Threaten legal action over human rights violations

2008: Sark capitulates, dismantles feudal system after 443 years

December 2008: First democratic election—Barclay-backed candidates lose

Next day: Barclays fire all 140 workers (roughly 1/6th of population)

Aftermath: Some rehired, but message sent: billionaires can punish democracy as effectively as feudal lords ↩

What the Seigneur kept: The pigeon monopoly (still law!), the title "Seigneur of Sark," significant land ownership, and ceremonial status as vassal to the Crown. What he lost: political veto power, ability to appoint officials, control over divorces and property transfers, the unspayed dog monopoly, and primogeniture inheritance rules. ↩

The dairy farm failure: The economics are brutal—tiny customer base, no economies of scale, transportation via tractor and boat, competing against mainland dairy arriving by ferry. Medieval infrastructure meets modern capitalism, and medieval loses every time. ↩

Sark vs other micro-economies: Compare to Monaco (39,000 people, massive wealth), Liechtenstein (39,000, industrialized financial hub), or San Marino (34,000, tourism plus manufacturing). Those are boutique economies with land borders and diversified industries. Sark is too small (500 vs 30,000+), too isolated (50-minute ferry), and dependent on tourism alone. It's less a functioning microstate than an expensive theme park that people happen to live in. ↩

What you'll actually see in Sark's sky: In 2011, Sark became the world's first Dark Sky Island—complete absence of light pollution. The Milky Way stretches horizon to horizon. Thousands of stars visible to the naked eye (most Europeans see only a few hundred). Meteors constantly streak overhead. Planets glow so bright they cast shadows. Moon craters visible without a telescope. La Coupée ridge is considered one of Earth's best sites for viewing Scorpius, Sagittarius, Lyra, and Cygnus. The island operates an observatory with a 12" Meade telescope for public sessions. Only ~1% of Europe still has genuinely dark skies—Sark's medieval stubbornness accidentally preserved what industrialization destroyed everywhere else. ↩

What's Next in Obscurarium?

What bizarre historical phenomenon should we investigate next? Drop us a line at [email protected].