Stop typing prompt essays

Dictate full-context prompts and paste clean, structured input into ChatGPT or Claude. Wispr Flow preserves your nuance so AI gives better answers the first time. Try Wispr Flow for AI.

August 22, 1485. Bosworth Field.

Henry Tudor's ragtag army1 has just killed Richard III and ended the Wars of the Roses. The last Plantagenet king lies dead in a ditch, his crown fished out of a hawthorn bush2 Henry VII—as he'll now be called—marches toward London to claim his throne.

His soldiers are already dying.

Not from battle wounds. From something else. Within three weeks of Henry's arrival in London, a disease broke out that would kill several thousand people by late October, including two lord mayors, six aldermen3, and three sheriffs.

The symptoms: sudden cold shivers, violent headache, severe pains in the neck and limbs, followed within hours by profuse sweating, rapid heartbeat, delirium. Death or recovery typically occurred within 24 hours. Sometimes people died in two hours.

They called it the Sweating Sickness. Sudor Anglicus. The English Sweat.

And it did something no disease in recorded history had ever done: it killed the rich more than the poor.

Bad Air, Bad Places: The Logic of Miasma

For two thousand years, the pattern had been consistent, predictable, almost a law of nature: poverty kills.

Diseases festered in cramped slums where families of ten shared single rooms and sewage ran in the streets. Typhus spread through filthy quarters where lice bred in unwashed clothing and bodies pressed together in tenements. Cholera thrived where contaminated water mixed with human waste.

The rich died too, of course. But they died less. They had space. They had private wells. They could flee to country estates when epidemics struck cities. They could quarantine themselves in manor houses with clean linens and servants to tend them.

Medieval and Renaissance physicians understood disease through the theory of miasma—corrupted air rising from decay. The ancient Greeks had named it. Roman physicians traced fevers to marshes and stagnant water. Medieval doctors wore beaked masks stuffed with herbs and flowers to filter the poisoned air of plague cities.

It wasn't stupid. It was observational medicine based on what everyone could see: disease clustered where filth accumulated. The air in slums smelled bad. The air around swamps felt unhealthy. The correlation was obvious, even if the causation was wrong.

A man holding his noise to avoid breathing in miasma.

And here's the thing: they were half-right. Diseases DO spread through the air—just not through "corrupted" air from decay. Measles, tuberculosis, influenza, and dozens of other diseases spread through tiny respiratory droplets that sick people exhale, cough, or sneeze into shared air. Poor ventilation concentrates those invisible particles. Crowded spaces amplify transmission. Fresh air and open windows genuinely help—not because they disperse miasma, but because they disperse aerosols containing actual pathogens.

The miasma theorists were observing real patterns. They just didn't understand the mechanism. It wasn't the smell of rot that killed. It was invisible particles from infected lungs, a concept that wouldn't be understood until the 20th century.

And crucially, the pattern always held: the conditions that accompanied urban poverty—overcrowding, poor sanitation, malnutrition, inability to rest when sick, exposure to infected people—these killed. Consistently. Predictably.

Until they didn't.

The Disease That Preferred Palaces

The Sweating Sickness appeared five times in Tudor England—1485, 1508, 1517, 1528, and 1551—before vanishing forever. Each outbreak followed the same bizarre pattern.

The relatively affluent male adult population, particularly the clergy, seemed to suffer the highest attack rates. Lords died in their manor houses. Merchants collapsed in their counting rooms. University students dropped dead in Cambridge colleges. Not one parish had a majority of women buried from the disease, and in two sample records more than 80 percent of burials were of males.

Meanwhile, the poor—living in the same filthy, crowded conditions that amplified every other disease—were somehow less affected.

This wasn't just unusual. This was medically impossible according to everything physicians understood about how disease worked.

The theories ranged from plausible to absurd. Some blamed God's punishment for supporting Henry VII's usurpation5 (ignoring that later outbreaks occurred under different kings). Some thought miasma from disturbed soil after the Wars of the Roses battles. Some believed rich people's soft living made them vulnerable—too much rich food, too little physical labor, bodies weakened by luxury.

The most likely modern theory involves hantavirus from rodents disturbed during the massive post-war building boom. Rich people were constructing new manor houses and expanding estates. Poor people lived in the same hovels they'd always inhabited. New construction meant disturbing rodent nests. Disturbed rodents meant aerosolized virus in the dust breathed by workers and wealthy owners inspecting their new properties.

The clergy fit this pattern perfectly: monks and priests worked in old stone monasteries, churches, and priories—buildings with grain stores, libraries full of manuscripts, and food cellars that attracted rodents. They spent their days indoors in enclosed, poorly ventilated spaces copying texts, conducting services, and administering church properties. When Henry VIII began dissolving monasteries in 1535, these ancient buildings were emptied, renovated, or demolished—disturbing centuries of accumulated rodent populations. Perfect conditions for hantavirus exposure.

It's elegant. It fits the pattern. It explains why the disease appeared with Henry Tudor's army (which had camped in the Welsh marshes—a probable reservoir), why it targeted the wealthy (who were building), and why it disappeared (once the building boom ended and survivors developed immunity).

But we'll never know for certain. The disease vanished before anyone could study it properly.

The Sweating Sickness in the 16th century. Euricius Cordus (1486-1535)

Learn AI in 5 minutes a day

What’s the secret to staying ahead of the curve in the world of AI? Information. Luckily, you can join 2,000,000+ early adopters reading The Rundown AI — the free newsletter that makes you smarter on AI with just a 5-minute read per day.

Henry's Love Letter (And His Second-Best Doctor)

The fourth outbreak—1528—hit during the most politically volatile moment of Henry VIII's reign. The king was obsessed with Anne Boleyn. His marriage to Catherine of Aragon was crumbling. The entire Tudor succession hung in the balance.

Then, in June, the Sweat returned.

Henry VIII, always obsessive about his health, bolted from court and began moving from palace to palace to stay ahead of infection. The French Ambassador Du Bellai wrote: "One of the filles de chambre of Mlle Boleyn was attacked on Tuesday by the sweating sickness. The King left in great haste, and went a dozen miles off."

Anne Boleyn herself fell ill at Hever Castle, the Boleyn family estate in Kent.

Henry, from a safe distance, wrote her a love letter. It's one of the few surviving letters in his own hand to Anne, and it reveals everything about Henry's character:

"There came to me suddenly in the night the most afflicting news... The first, to hear of the illness of my mistress, whom I esteem more than all the world, and whose health I desire as I do my own, so that I would gladly bear half your illness to make you well... The third, because my physician, in whom I have most confidence, is absent at the very time when he might do me the greatest pleasure... yet for want of him I send you my second."

Let's unpack that. Henry would "gladly bear half your illness"—not all of it, just half. Very generous. And he's sending his second-best physician. Dr. William Butts. His primary physician was away, so Henry kept him for himself and dispatched Butts to Hever with the love letter.

The woman he claims to love more than all the world, fighting a disease with a 50% mortality rate, gets the backup doctor.

Anne survived. Others weren't so lucky. Thomas Cromwell lost his wife and two daughters. William Carey—Mary Boleyn's husband—died. William Compton, Henry's Groom of the Stool4, died.

William Carey by Lucas Horenbout

The court was paralyzed with terror.

Du Bellai wrote: "This disease is the easiest in the world to die of... There is no need for a physician: for if you uncover yourself the least in the world, or cover yourself a little too much, you are taken off without languishing."

The treatment advice was absurd and contradictory: Stay in bed for 24 hours without moving. Don't sleep or you'll die. Sweat it out with extra blankets. Don't sweat too much or you'll die. Drink herbal mixtures. Don't drink anything. Let blood. Don't let blood.

No one knew what they were doing. People died anyway.

Here's the strange part: Cardinal Wolsey contracted the illness and survived four separate attacks in one month during the 1517 outbreak. Four. In one month. Either Wolsey had an extraordinary immune system, or the disease had unusual patterns of relapse and remission, or chroniclers were counting something else entirely. We don't know.

Cardinal Wolsey

The Man Who Made His Fortune From Fear

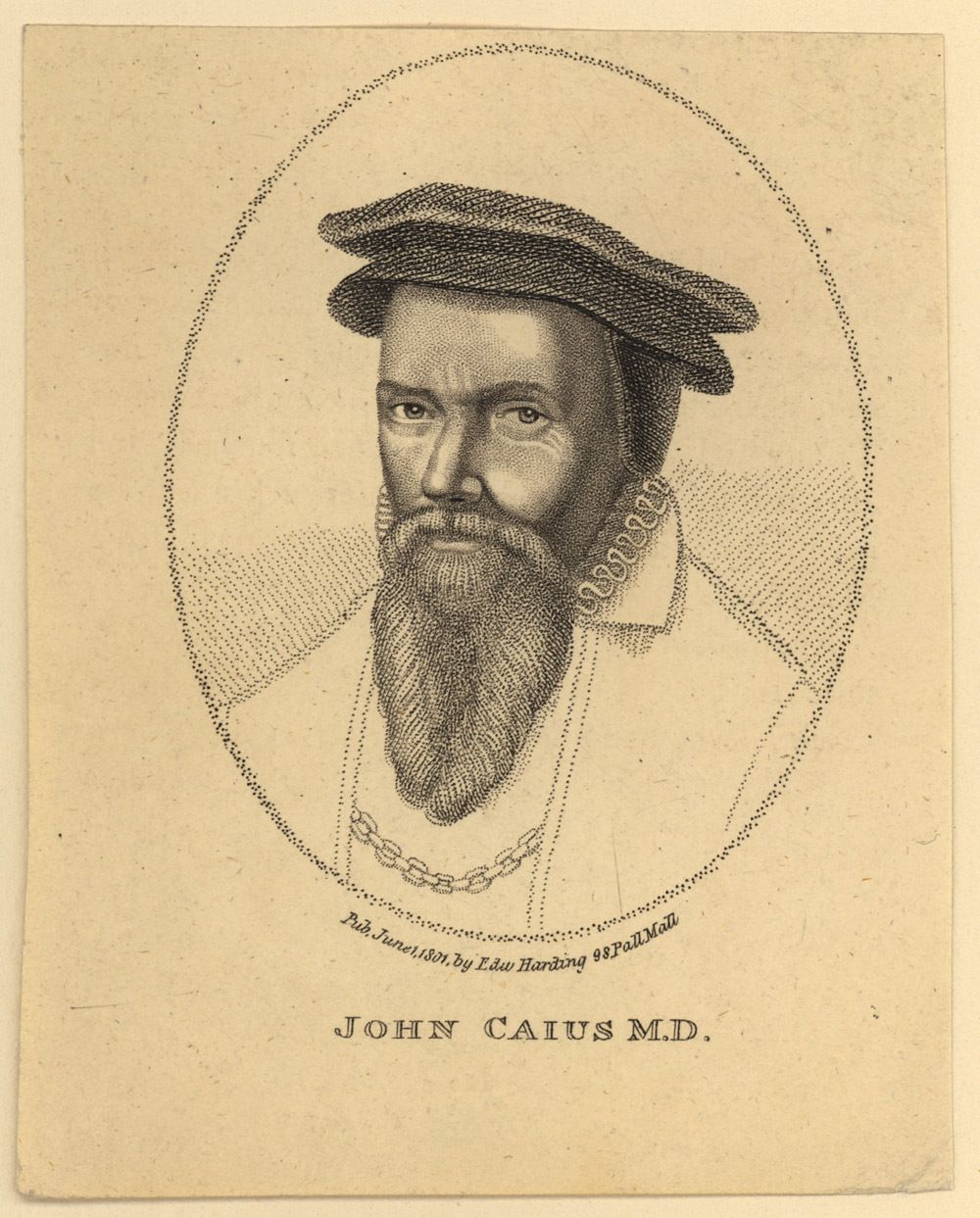

In 1551, when the final outbreak occurred, a physician named John Caius was in Shrewsbury. Instead of fleeing like most wealthy people, he stayed. He observed. He took notes. He treated terrified patients who would pay anything to survive.

The following year, he published "A Boke or Counseill Against the Disease Commonly Called the Sweate, or Sweatyng Sicknesse" (1552), establishing himself as the expert on England's most terrifying disease.

It's a fascinating document—part medical observation, part public health pamphlet, part advertisement for his expertise. He described symptoms in vivid detail. He noted that survivors who made it past 24 hours usually recovered. He blamed the disease on "dirt and filth" (wrong, but standard medical theory).

Most importantly, he positioned himself as the go-to expert on the Sweat.

John Caius

Caius (who'd Latinized his surname from Keys when he returned from medical training in Italy—fashionable physicians did that) served as physician to Edward VI, Mary I, and Elizabeth I. He became president of the Royal College of Physicians. In 1557, he enlarged his old college's foundation, changed the name from "Gonville Hall" to "Gonville and Caius College," and endowed it with estates worth £1,834—equivalent to about £680,000 today.

Where did a physician in the 1550s get that kind of money? Terrified rich people, mostly. People who would pay anything to the man who'd written the book on the Sweat.

Gonville and Caius College still exists. It's one of the wealthiest colleges at Cambridge. You can visit the Gates of Humility, Virtue, and Honour that Caius designed. You can see his tomb: Fui Caius—"I was Caius."

A disease we still don't understand paid for a Cambridge college that still educates students 470 years later.

The Other Disease That Vanished

While the Sweating Sickness was killing Tudor England's elite, another disease was quietly disappearing from Europe: leprosy.

This one we can explain.

Medieval leprosy had been a catastrophe. In certain areas, 1 in 30 people were infected. An estimated 19,000 leprosy hospitals existed across Europe in 1200. The disease disfigured. It killed slowly. It terrified everyone.

Then, rather abruptly and for unknown reasons at the time, the incidence began to decline between 1200 and 1300. By the turn of the 16th century—just as the Sweating Sickness was appearing—leprosy mysteriously disappeared and never returned.

Why?

Humans evolved resistance. And here's the fascinating part: people infected with tuberculosis were cross-immunized against leprosy. As TB spread through crowded medieval cities (following the normal pattern of poverty and disease), it inadvertently protected populations against leprosy.

We know this because we've extracted Mycobacterium leprae DNA from medieval skeletons and compared it to modern samples. The disease didn't change. We did. Our immune systems adapted. The conditions that spread TB (crowding, poor ventilation, close contact) accidentally vaccinated populations against a different bacterium.

Leprosy vanished because of evolution, ecology, and cross-immunity—factors that wouldn't be understood for another 500 years, but which operated nonetheless.

The Disease That Didn't Vanish (But We Wished It Had)

Not all mysterious plagues disappeared so conveniently.

In 1770, Moscow was struck by bubonic plague—the same disease that had killed a third of Europe during the Black Death. By the time it ended in 1772, between 52,000 and 100,000 people had died, roughly one-sixth to one-third of Moscow's population.

The plague itself wasn't mysterious. By 1770, physicians understood it was contagious, though they didn't yet know about fleas and rats. What was remarkable was the human response.

Russian Orthodox believers in Moscow flocked to kiss an icon of the Mother of God, believing it would protect them from plague. The authorities, understanding that hundreds of people kissing the same icon was perhaps not ideal disease prevention, removed it.

This sparked the Plague Riot of September 1771. A mob of thousands, led by a group of shopkeepers and minor clergy, stormed the Kremlin demanding the icon's return. They murdered Archbishop Ambrose when he refused to bring it back. The riot was only suppressed when artillery was brought into Moscow and the military killed hundreds.

Plague Riot in 1771 Russia

Catherine the Great, ever the pragmatic autocrat, had a memorable response to the church bell that had rung the alarm calling the rioters to assemble: she ordered its tongue cut out. The bell was silenced for 30 years as punishment.

The plague eventually subsided—not through prayer or icon-kissing, but through quarantine and the normal pattern of epidemic burnout. Moscow implemented strict isolation measures, burned infected houses, and prohibited large gatherings. It worked, as such measures tend to do, though not before tens of thousands had died.

The fascinating part isn't that the plague struck—plague had been cycling through human populations for centuries. It's that even in 1770, after the Enlightenment, after centuries of plague experience, the response combined medieval religious fervor (icon-kissing) with early modern science (quarantine) with spectacular violence (murdering the archbishop).

We knew enough to quarantine. We didn't know enough to stop kissing the plague-spreading icon.

Forty Days of Waiting

The word "quarantine" itself comes from exactly this kind of trial-and-error disease management.

In 1377, the city of Ragusa (modern Dubrovnik, then under Venetian control) implemented a thirty-day isolation period—trentina—for ships arriving from plague-affected areas. By 1423, Venice had established a more systematic approach: ships from infected ports had to anchor at designated islands in the lagoon for forty days before passengers and cargo could enter the city.

Forty days. Quaranta giorni in Venetian Italian. Hence: quarantine.

Why forty? Two reasons. First, purely practical: Venetian authorities realized through observation that about forty days was sufficient to determine if a ship's crew was diseased. The bubonic plague had roughly a 37-day period from infection to death, so forty days covered the incubation period plus time for symptoms to appear or not.

Second, religious: forty was a good Christian number. Forty days of Easter. Forty days of Lent. Forty days of the flood. Round, sacred, memorable.

Venice established two islands: Lazzaretto Vecchio (Old Lazaret) for treating the actively sick, and Lazzaretto Nuovo (New Lazaret) for quarantining potentially exposed but currently healthy people. The system was permanent, government-run, continuously monitored, and operated until Napoleon conquered the region in 1797.

It was one of the first systematic public health systems in Europe, created without understanding why it worked—just that it did.

Venice's plague doctors wore those iconic beaked masks, stuffed with herbs and spices, believing the aromatic compounds would filter "corrupted air." They were practicing miasma theory. The masks probably did nothing against plague (which spreads through flea bites and aerosol droplets from pneumonic cases, not miasma). But the quarantine system worked anyway, because you don't need to understand germ theory to understand that keeping sick people away from healthy people reduces transmission.

What We Still Don't Know

Here's what makes disease history so humbling: we're still guessing about fundamental patterns.

The Sweating Sickness appeared out of nowhere, killed thousands, and vanished forever. We have theories—hantavirus from construction dust, an extinct flu strain, relapsing fever, something we've never identified. But we don't know. The disease didn't leave DNA in teeth or bones like plague did. It didn't leave characteristic lesions like smallpox. It just left descriptions in letters and chronicles.

All we know is that for 66 years, Tudor England lived in terror of something that could kill in hours, that seemed to prefer the wealthy and educated, that came and went without warning, and that doctors were completely unable to treat, prevent, or understand.

Robert Seymour.

Leprosy vanished because humans evolved and TB provided cross-immunity—but this was pure chance. Medieval physicians had no idea why leprosy was declining. They credited better hygiene, divine intervention, improved morals. They were guessing.

Even COVID-19, with all our modern epidemiology and genetic sequencing and global surveillance, initially baffled us. Yes, it eventually followed the age-old pattern—poverty, overcrowding, and lack of healthcare access meant higher death rates. But in the very early stages, infections were concentrated in higher income groups involved in international travel and social activities. Richer countries with more airplane connections got hit first and harder initially.

For a brief moment, COVID looked like it might be another "backwards disease" like the Sweating Sickness. Then it reverted to form. Poverty killed, as it almost always does—not because poverty itself is pathogenic, but because the conditions that often accompany poverty in densely populated areas (overcrowding, inability to isolate, continued exposure to infection, limited medical access) create perfect conditions for disease transmission.

The Pattern That Explains Nothing

The Sweating Sickness epidemics were unique compared with other disease outbreaks of the time. Whereas other epidemics were typically urban and long-lasting, cases of sweating sickness spiked and receded very quickly, significantly affecting rural populations as well as cities.

That's backwards. Normally, epidemic diseases spread slowly from person to person in cities, then radiate outward. The Sweat appeared simultaneously across multiple locations, hit rural areas hard, and disappeared within weeks.

The irregular intervals between the five epidemics—22, 10, 11, and 23 years respectively—suggest an ecological or meteorological trigger, not human-to-human transmission. Something environmental.

But what? Rodents? Grain storage? Weather patterns? Construction projects? All of the above? We don't know.

And that's the humbling truth: it's a mystery that can never be solved. The disease is gone. The bodies are dust. The evidence is limited to a few dozen contemporary accounts and one detailed pamphlet by a physician who was absolutely guessing.

What We're Left With

Anne Boleyn recovered from the Sweat and went on to marry Henry VIII, give birth to Elizabeth I, and lose her head on Tower Green in 1536.

Thomas Cromwell, who lost his wife and daughters to the disease in 1529, would orchestrate Anne's execution and then lose his own head in 1540.

John Caius died in 1573, wealthy and respected, with a Cambridge college bearing his name.

Henry VIII died in 1547, paranoid about illness to the end, having outlived five of his six wives.

The Sweating Sickness died in 1551 and was never seen again.

Medieval leprosy vanished around the same time, though for completely different reasons we didn't understand until extracting ancient DNA from skeletons centuries later.

Moscow's plague bell hung silent for thirty years, its tongue cut out for calling the riot.

Venice's quarantine islands operated for nearly 400 years, proving that effective public health measures don't require correct theory—just consistent observation and enforcement.

Medicine advances. We've conquered smallpox, nearly eliminated polio, turned HIV from a death sentence to a manageable chronic condition. We can sequence a virus's genome in days, track its spread in real-time, design vaccines in months.

But we still can't explain the Sweating Sickness. We still argue about why leprosy vanished (even though the genetic and immunological evidence is solid, the timing and mechanism remain debated). We still discover diseases we didn't know existed—Legionnaires' disease in 1976, HIV in 1981, SARS in 2003, COVID-19 in 2019.

Every time we think we understand the rules of how disease works, something breaks them.

And sometimes—like the Sweating Sickness—it breaks them so thoroughly that centuries later, with all our technology and knowledge, we're still left staring at historical accounts thinking: What the hell was that?

Tech moves fast, but you're still playing catch-up?

That's exactly why 100K+ engineers working at Google, Meta, and Apple read The Code twice a week.

Here's what you get:

Curated tech news that shapes your career - Filtered from thousands of sources so you know what's coming 6 months early.

Practical resources you can use immediately - Real tutorials and tools that solve actual engineering problems.

Research papers and insights decoded - We break down complex tech so you understand what matters.

All delivered twice a week in just 2 short emails.

What's Next in Obscurarium?

What bizarre historical phenomenon should we investigate next? Drop us a line at [email protected].

1 Henry Tudor invaded England with approximately 2,000 men, mostly French mercenaries and Welsh supporters—a tiny force compared to Richard III's army of 10,000-15,000. He won through a combination of battlefield betrayals and sheer luck.

2 According to Tudor chronicles, Richard III's crown fell from his head during the battle and was found in a hawthorn bush. Lord Stanley placed it on Henry's head on the battlefield—though this story may be propaganda designed to legitimize Henry's claim to the throne.

3 Aldermen were senior members of London's city council, typically wealthy merchants who governed the city's wards. Their deaths signaled that the disease was hitting the upper classes particularly hard.

4 The Groom of the Stool was one of the most prestigious positions at the Tudor court—essentially the king's personal attendant who managed his toilet and hygiene. Because of the intimate access to the king, Grooms of the Stool often became trusted advisors and wielded considerable political influence. Compton was one of Henry VIII's closest friends.

5 Henry Tudor's claim to the throne was legally weak—he was descended from John of Gaunt through an illegitimate line that had been explicitly barred from succession. He won the crown by killing Richard III in battle and marrying Elizabeth of York (the Yorkist heir) to legitimize his rule. Many contemporaries, particularly Yorkist supporters, considered him a usurper who'd seized power by force rather than rightful inheritance.